Grocery prices and mortgages in cities are going through the roof. You’ve decided to go rural and you are looking at the options. What about an inflatable concrete home like the one built by Robert Downey Junior? If you’ve chosen this path, over superadobe, you wonder, how can you make the numbers work and make it sustainable? Read our article on inflatable concrete homes and how much they cost.

Let’s start: Imagine buying a modest rural plot, somewhere near Sudbury, Ontario, or in the Sierra foothills of California—and building a 1,000-sq-ft (93 m²) home using an inflatable-shell method like that created by Binishell. A flat, fabric form is inflated on-site and filled with a low-carbon concrete mix that hardens into a seamless, dome-like shell.

Binishell Robert Downey Junior home in Malibu

Inside, the walls are finished and insulated with hempcrete, a breathable, carbon-negative material that stores carbon as it cures. The entire build aims to reduce dependence on expensive mortgages, rising energy bills, and urban living costs while embodying resilience and ecological balance.

Because there’s no heavy scaffolding or formwork, construction is quick and more or less clean. Inflation and concrete pumping take a day; curing takes a week or so. The costs?

Ontario: Shell cost ≈ US $25–40 / sq ft.

California: Shell cost ≈ US $45–60 / sq ft.

After adding foundations (will you have a finished basement?), utilities, and finishes, total cost lands between US $120–16/sq ft—far below conventional rural builds, which often exceed US $250/sq ft. The finished home is highly energy-efficient: thick hempcrete walls and thermal-mass concrete stabilize interior temperature, lowering heating and cooling bills by up to 50%. Over 15 years, savings on mortgage and energy can reach tens of thousands of dollars. For people who want to start a regenerative farm or an online business in the country, this is a no-brainer.

Inflatable concrete house

Concrete’s carbon footprint is its biggest flaw, but newer mixes cut emissions dramatically. Take calcined-clay blends (LC³), fly-ash or slag substitutes, and carbon-mineralization technologies like CarbonCure which can reduce CO₂ output by 40 %. In California, renewable-energy credits further offset embodied carbon; in Ontario, pairing solar panels or micro-hydro with low-carbon materials can make the structure nearly net-zero.

Look out for hidden costs and restrictions. Some people prefer to buy land in unorganized townships to avoid too much government oversight. That doesn’t mean you can do what you want. Permits are still needed. In Ontario, you need a building permit for any new structure over 10 square meters (108 sq ft), or for any structure, including sheds, over 15 square meters (sq ft), depending on the municipality.

Hempcrete adds another layer of sustainability, absorbing CO₂ during curing and improving indoor air quality. Together, these materials turn a traditionally high-carbon building type into a model of circular design. Hempcrete is also fire resistant, and added bonus for people in forest fire prone areas in California.

The biggest barrier today in new sustainable building isn’t technology—it’s building codes. Inflatable concrete shells fall outside most standard residential classifications. In both provinces and states, permits require engineering certification, structural testing, and often a variance from conventional framing standards. Builders must collaborate with local inspectors early, providing proof of structural integrity, insulation values, and fire ratings. If you are into dealing with those hassles you can create a model home for your neighbors to follow.

Inflatable-shell homes offer a credible path to affordable, durable, and lower-carbon living. For those willing to navigate permitting and pioneer new methods, this approach could define the next generation of rural housing—fast to build, low in cost, and light on the planet. It always takes the first movers to start new dreams.

Inflatable Concrete Domes in Canada

The Monolithic Dome Institute (MDI) has helped bring air-formed concrete construction to Canada, proving that dome-shaped, energy-efficient homes can thrive even in cold northern climates. Its method, known as the Monolithic Dome system, relies on an inflatable air-form, steel-reinforced concrete, and foam insulation to create one continuous, highly durable shell.

In Yorkton, Saskatchewan (shown below), Canadian Dome Industries built a 40-foot (12.2 m) hemispherical home that demonstrates the system’s practicality and strength.

Another dome, located in central Alberta, measures 55 feet in diameter and was built off-grid in 2005. This structure uses passive-solar orientation, thick insulation, and thermal-mass concrete to remain comfortable year-round, reducing energy demand in both heating and cooling seasons.

Yorkton Dome in Canada

Yorkdon Dome, finished

Construction begins with a flexible Airform membrane anchored to a circular foundation. The membrane is inflated to the desired dome shape, and workers spray its interior with polyurethane foam to form a stable surface. Steel reinforcement is attached to the foam, and layers of shotcrete (sprayed concrete) are applied, hardening into a self-supporting structure. The finished shell functions as roof, walls, and insulation all in one piece—eliminating many of the weak points found in conventional buildings.

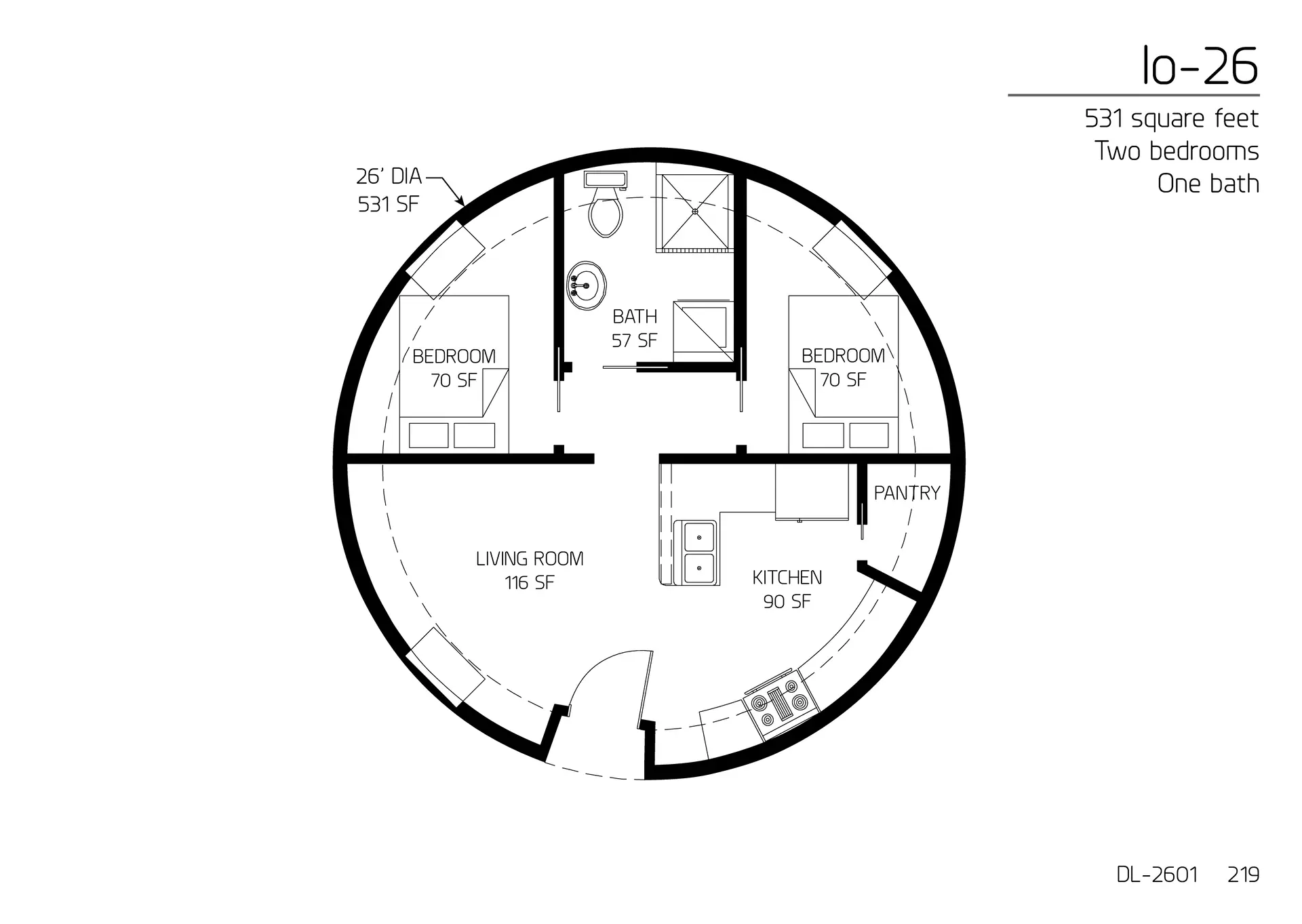

Monolithic dome planning

According to the Monolithic Dome Institute, these domes use up to 50% less energy than standard homes. Their rounded shape sheds wind and snow efficiently, making them highly resistant to storms, mold, fire, and pests—key advantages in Canada’s variable climate. We just need a new shape of bed to fit a square in a rounded room.

While MDI’s technique differs from newer “inflatable concrete bladder” methods—where the form itself is filled with concrete rather than sprayed over—the principle remains the same: air replaces formwork.

Inside a Binishell home

These Canadian dome homes demonstrate that air-formed, reinforced concrete shells are a proven, climate-resilient housing solution and a foundation for more sustainable, low-carbon building methods in the future. With builds for industry, the Monolithic Domes aren’t as pretty as Binishells.