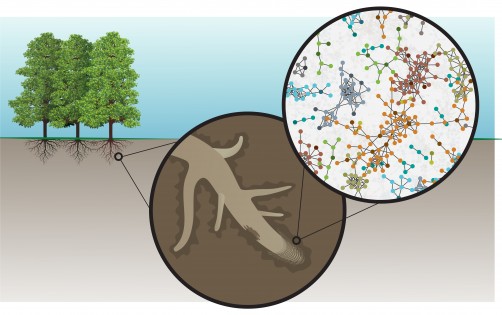

We tend to think of forests as quiet places—but beneath the soil, there’s a bustling network of chemical conversations taking place. It’s part of what some scientists call the “wood wide web”—a vast underground communication system that connects plants, fungi, and microbes in complex, symbiotic ways. It’s been shown that plants can speak. This new study might help us decode what they are saying.

Now, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) have uncovered new insights into this hidden language. By studying the molecular “words” that tree roots send into the soil, they’ve created one of the most detailed maps yet of underground plant communication—one that could revolutionize how we grow food and bioenergy crops.

As plants grow, their roots don’t just absorb nutrients—they release a rich array of organic chemicals into the soil, a process known as rhizodeposition. These secretions act like messages or invitations to microbes and fungi, encouraging cooperation, support, or sometimes defense.

“Plants form relationships with microbes like bacteria and fungi that help them survive tough conditions like drought or poor soil,” said Dr. Paul Abraham, co-lead of the study at ORNL. “But we’re only beginning to understand the full vocabulary of these underground interactions.”

How plants talk underground: unlocking the secrets of the wood wide web.

To decode this chemical language, ORNL researchers focused on poplar trees, which are being studied as future bioenergy crops. They grew two types of poplar under different conditions—some with extra nutrients, some without—and collected samples from their roots at different growth stages.

Instead of looking for specific molecules they already knew, scientists used a technique called untargeted metabolomics, which allowed them to capture everything the plants were saying, so to speak.

“This approach lets us detect a much broader range of chemical diversity,” Abraham explained. “We’re finding unexpected or previously unrecognized compounds that may play critical roles in soil and plant systems.”

A molecular treasure trove

Close-up of the interactive sound garden at the University of Melbourne’s “Song of the Cricket” installation. Visitors walk among embedded speakers and vegetation while the gentle song of crickets reimagines Venice’s lost natural soundscape.

What they found was a treasure trove of compounds—some never identified before. Each plant produced different chemical profiles depending on its genes, environment, and age. These findings suggest that plants tailor their messages depending on who they’re talking to—whether they’re calling for help, warning of threats, or optimizing partnerships.

“This kind of insight helps us breed or engineer crops that are not only higher-yielding, but also more resistant to climate stress,” Abraham said.

Mushrooms, microbes, and machine learning?

a basket of mushrooms collected in Ontario, Canada

Why does this matter? The underground networks built by fungi and bacteria are essential for healthy ecosystems—and for our ability to grow resilient crops in a changing climate. Fungi, in particular, act as “middlemen”, connecting roots across distances and helping move nutrients, water, and even chemical signals between plants.

To better understand this complex web, ORNL is now looking to AI and machine learning. “The chemical space we’re measuring is vast,” Abraham said. “Most of the molecules we detect can’t be confirmed using existing reference standards.”

In other words, there are too many molecules and not enough names. That’s where artificial intelligence will step in—to help identify unknown compounds and unlock new insights into how plants and microbes interact.

The ORNL team’s research, published in Plant, Cell & Environment, could eventually lead to crops that communicate more efficiently with beneficial fungi and bacteria—reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers and helping build a more sustainable agricultural system.

“Nature already has a smart underground network,” says Karin Kloosterman, editor of Green Prophet who founded an AI company Flux to listen to the language of plants: “Our job is to listen, decode it, and learn how to work with it.”