An ancient Qanat system in Persia. Spread throughout the arid Middle East, these systems predated Roman aqueducts but the historical narrative isn’t told

As tensions over water intensify across Iraq and the wider Middle East, the 5th Baghdad International Water Conference has cast a timely spotlight on the country’s fragile water future—and its ancient hydrological past.

Held in the heart of Mesopotamia—where early civilizations once mastered the art of water management—the conference drew regional experts and leaders to Baghdad to confront a crisis that’s becoming more urgent by the year: water scarcity. With rivers running dry and modern agricultural systems straining under the pressure, Iraq finds itself at a crossroads between its hydraulic heritage and an increasingly parched present.

The Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman are ancient water channels from 500 AD located in the regions of Dakhiliyah, Sharqiyah and Batinah. However, they represent a type of irrigation system as old as 5000 years in the region named as Qanat or Kariz as originally named in Persia.

The land between the Tigris and Euphrates was once a wellspring of invention. Thousands of years before modern irrigation, the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians carved canals, engineered flood basins, and developed qanat systems—ingenious underground channels that carried water from mountain springs to distant farms.

These systems weren’t just technical achievements; they were the lifeblood of cities, temples, and trade. Water determined everything—from the rise of empires to the poetry etched into clay tablets.

Iraq marsh people know how to live with water

But today, the once-mighty rivers that sustained those ancient cultures are shrinking. Dams upstream, salinization, climate shocks, and mismanagement have left Iraq’s water infrastructure overburdened and outdated. Agriculture now consumes over 90% of Iraq’s water, yet crop yields are falling. Some estimates suggest that without reform, wheat and barley yields could drop by half by 2050.

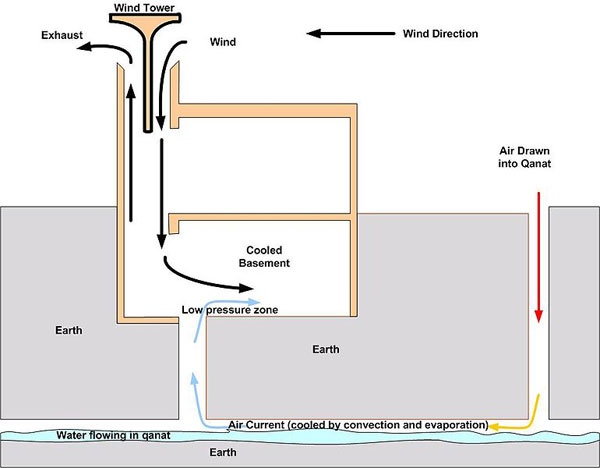

How a qanat works

These aren’t just numbers. Iraq’s rural communities—many of whom still rely on traditional farming—are already being uprooted by water shortages. Marshlands, once teeming with biodiversity and cultural life, are evaporating. The disappearance of water from ancestral lands threatens to sever ties to history, religion, and identity.

This has ignited conflict—not just between nations sharing river systems, but within Iraq itself. Disputes over water rights are rising, and in some areas, violence has already erupted. A younger generation, particularly women and smallholder farmers, are being left with few options: adapt or leave.

The Persian Qanat: Aerial View, Jupar

Despite the severity of the situation, Iraq isn’t without solutions. The country is rediscovering the value of its past while cautiously embracing modern technologies. Sometimes, like in Afghanistan the outcome can be dubious. Opium farmers now use solar powered water pumps to cultivate poppies.

Solar panels are a boon for the planet but they are now fueling bumper crops of poppies for the opium trade. Via the NY Times.

Remote sensing tools, such as those used in the WaPOR programme, are helping farmers monitor water use and optimize irrigation. Solar-powered systems, being piloted in neighboring Egypt and Tunisia, offer hope for regions where diesel pumps are no longer viable. Community-led water user associations—reminiscent of ancient collective water governance structures—are being revived to restore trust and accountability.