The Majara Residence on Iran’s Hormuz Island has been praised internationally for its vibrant architecture and community narrative – even winning an Aga Khan Award for Architecture. But field research of the superadobe construction suggests the reality on the ground tells a different story: one of habitat loss, fragile ecosystems at risk, and a disconnect between architectural acclaim and ecological responsibility.

Architect Ronak Roshan Gilvaei who works on Sustainable Design, Architectural Restoration & Urban Renewal weighs in for this Green Prophet exclusive.

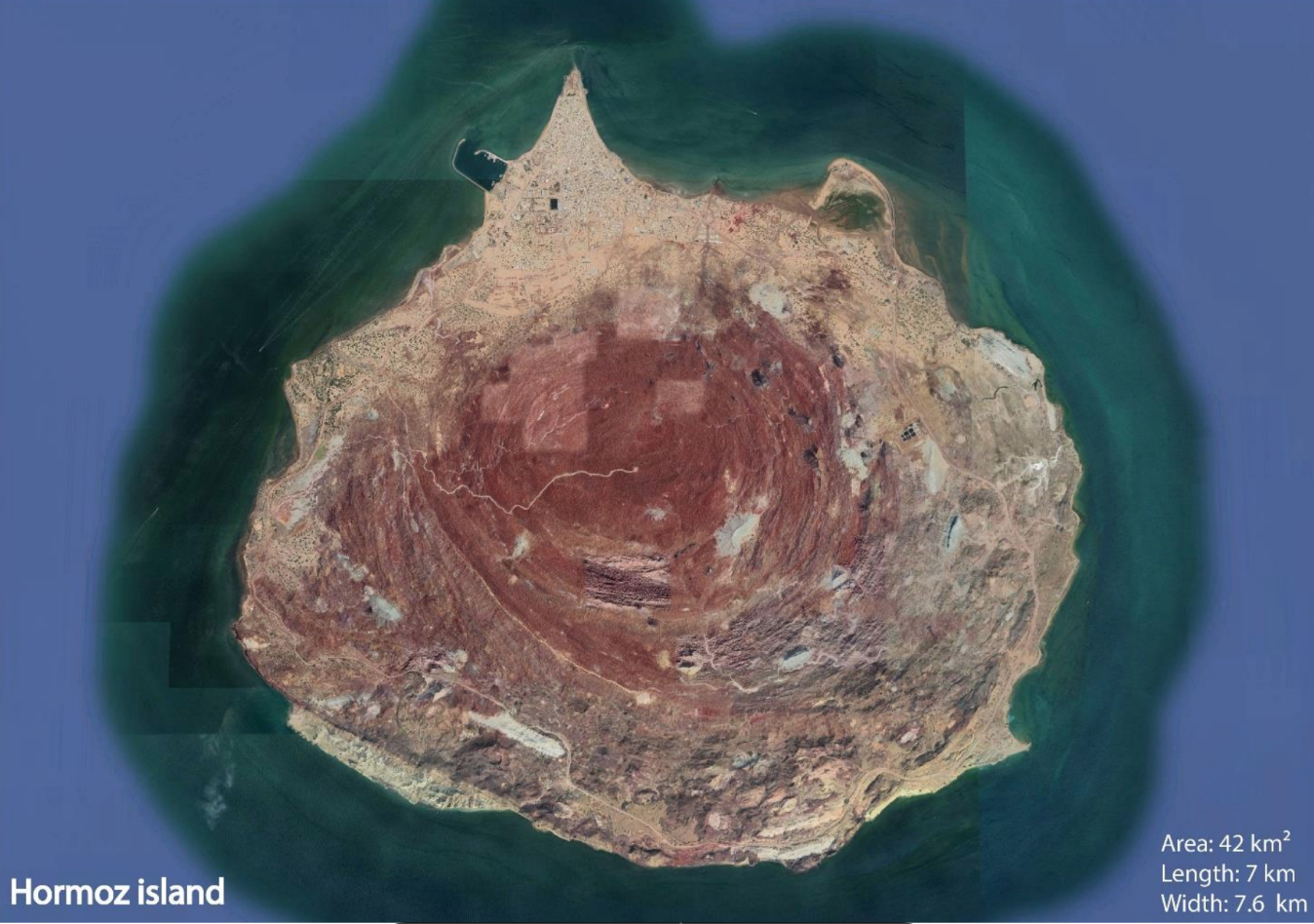

Hormuz Island – just 8 km from Bandar Abbas in Iran – is a geological wonder, famous for its rainbow-colored soil, unique marine biodiversity, and role as a nesting ground for critically endangered sea turtles. Studies have documented nesting by hawksbill and green turtles, especially on the island’s less accessible southeastern beaches.

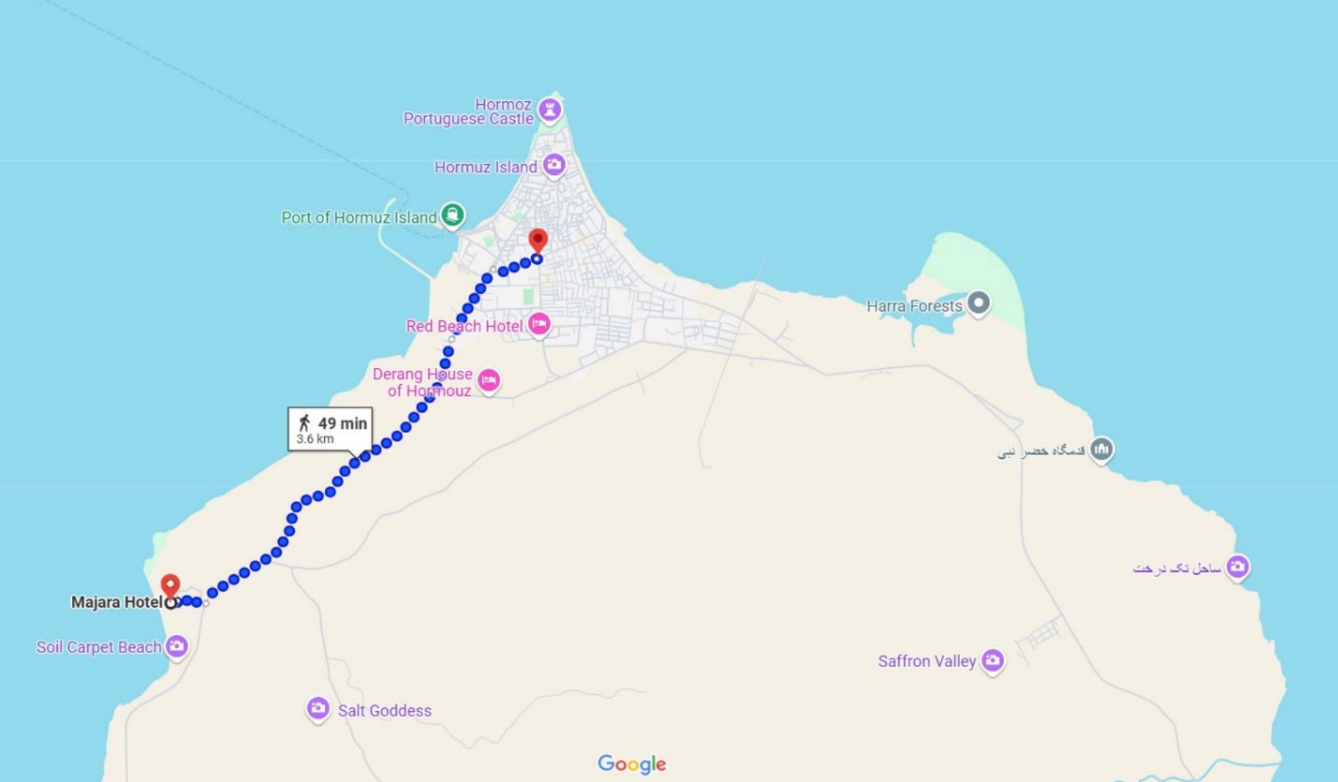

The Majara Residence (Persian: اقامتگاه ماجرا, where Majara translates to “adventure”) is a complex of roughly 200 colorful superadobe domes built on Hormuz Island as a seaside eco‑tourism project. Designed by ZAV Architects, it was completed around 2020.

At first glance and by its own descriptions, seems inspired by the philosophies of architects such as Nader Khalili, Francis Kéré, and Shigeru Ban. It could read as a model for sustainable development, particularly in its social dimension. However, my field visits and closer examination as an advocate for sustainable architecture and environmental conservation in Iran suggest the project’s execution contradicts the core principles of sustainability.

Its inclusion on shortlists for awards purportedly grounded in sustainability and environmental justice –– most recently the Aga Khan Award –– is surprising and concerning, especially given warnings and objections raised by activists, experts, and local communities in recent years. What has been labeled superficially as “revitalization” has, in practice, meant habitat invasion, erosion of indigenous values, and exploitation of local resources and people.

Like we learned from the Seychelles, these habitats require careful protection from light pollution, human traffic, and coastal development. Yet in recent years, tourism investors have eyed the same pristine stretches for high-profile projects, including the Majara Residence.

Its location – less than 80 metres from the high-tide line – puts it directly in sensitive turtle nesting zones. Standard conservation guidelines recommend at least a one-kilometre buffer from such areas. (Related: read the article on turtle conservation on Assomption Island.)

The consequences go beyond the hotel’s 1.5-hectare footprint. Artificial lighting can disorient hatchlings, while heavy machinery, coastal vegetation clearance, and increased visitor pressure threaten the wider ecosystem.

Digging deeper into science papers, Hormuz Island has played a vital role in the life cycle of two protected sea turtle species over the past decades. According to local research and the scientific paper “Nesting of Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) on Hormuz Island, Iran” (2011–2012), the island has been recognized as an active and potential protected habitat for the critically endangered hawksbill turtle in Iran. My field observations are all documented here, and are summed up for a quick read below.

This study mentioned above confirms regular nesting events, the relative success of hatchling survival, and the pristine condition of some of the island’s beaches. Additionally, the paper “Turtles in Iranian Beaches of Oman Sea during 2008–2010” (BEPLS, 2014) highlights the simultaneous presence of both hawksbill and green turtles on Iran’s southern coasts, including Hormuz, and notes that numerous nests of these species have been observed on the island’s shores in past years.

Although these studies lacked GPS-based nesting site mapping or granular habitat delineation to pinpoint exact nesting sites, this does not mean nesting does not occur in specific areas—rather, it underscores the need for more comprehensive research before any construction projects.

Most nesting activity has been clearly observed in the southeastern part of the island, an area less affected by human intervention due to its inaccessibility. However, in recent years, due to its visual appeal, some investors—including the current developer of the Majara Residence have aggressively pursued tourism development projects and new hotel constructions on this land.

Examples include last year’s proposals by Next Office and Studio KAT, which faced protests from activists and locals, halting their progress.

Destruction of Native Vegetation

Before construction, the site hosted resilient species like tamarisk, glasswort, and saltwort – plants that stabilise soil, reduce erosion, and withstand Hormuz’s extreme heat and salinity. Around 2.5 hectares of this vegetation was removed, with no ecological restoration plan in place.

ZAV Architects, in their project on Hormuz Island, identified the dominant vegetation as Prosopis juliflora (mesquite) and described it as an invasive species with deep roots that can harm biodiversity and infrastructure. However, from a scientific and ecological perspective, although mesquite is non-native and semi-invasive, it plays a vital role in stabilizing the soil, preventing erosion, and reducing desertification under the harsh environmental conditions of Hormuz.

Removing this plant without replacing it with native species and without an ecological management plan not only leads to habitat degradation but also contradicts the principles of sustainable development in sensitive areas, potentially causing further environmental damage. Therefore, the hotel’s action to remove the mesquite without considering these scientific and ecological factors is unjustified and harmful.

The hotel’s basic ozonation and composting systems lack advanced treatment needed for sensitive coastal zones. Without independent monitoring, there’s no way to confirm that wastewater meets safety standards. On an island without a municipal sewage network, any leakage could threaten coral reefs, seagrass beds, and turtle habitats.

The architects also promote the project as empowering Hormuz’s native residents. Yet reports indicate persistent economic challenges: water scarcity, high transport costs, and weak tourism management. The island’s own Sustainable Development Plan, developed with local participation, focuses on training, infrastructure, and sustainable livelihoods – a deeper approach than cultural tourism alone can provide.

Systems Thinking: A Missed Opportunity

As systems thinker Russell Ackoff argued, environmental challenges must be addressed holistically, recognising the interdependence of ecological, social, and economic factors. Successful examples, like wildlife restoration in Yellowstone Park, such as bringing back the wolves to restore the forest, show that strategic, science-led interventions can achieve balance.

On Hormuz, protecting sea turtles could have anchored an ecotourism model combining indigenous knowledge with conservation science – creating lasting benefits for both people and nature.

The Majara Hotel’s waste and sewage management system reportedly includes an ozonation unit with a daily capacity of 20 cubic meters, oil treatment up to 8 cubic meters, and compost production of 50 kg per day. However, the equipment used is basic, lacking advanced biological or physical-chemical treatment technologies. This is particularly alarming given the hotel’s location less than 70 meters from the shoreline, where any leakage or incomplete sewage treatment could severely endanger the island’s marine ecosystem.

According to studies by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 2020) and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP, 2019), hotel wastewater contains fats, detergents, nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus), micro-pollutants, and pathogenic microorganisms. Without advanced treatment processes—such as activated sludge reactors, biofilm systems, or ultrafiltration/nanofiltration membranes—this wastewater can degrade coral habitats, promote toxic algal blooms, reduce coastal water quality, and threaten public health (WHO, 2018).

The Majara Residence’s vibrant domes have captured global attention and won architectural accolades. But without rigorous environmental safeguards, it risks being remembered as an object lesson in how eco-tourism can turn extractive. Architecture awards that celebrate such projects without full ecological due diligence may inadvertently undermine the very sustainability principles they seek to promote.

Hormuz Island deserves development that honors its ecological fragility, cultural heritage, and the resilience of its people – not just in form and color, but in function and legacy.

Contact: [email protected] | ronakroshan.com

Designer Batoul Al-Rashdan, an engineer from Jordan, creates plant-based materials, which she turns into clothes and accessories. Via Batoul Al-Rashdan (UNEP) When Jordanian designer Batoul Al-Rashdan tells people she makes clothes out of ground olives and onion peels, she gets more than a few raised eyebrows. “It’s definitely a conversation starter,” laughs the founder of Jordanian fashion house Studio BOR.

Designer Batoul Al-Rashdan, an engineer from Jordan, creates plant-based materials, which she turns into clothes and accessories. Via Batoul Al-Rashdan (UNEP) When Jordanian designer Batoul Al-Rashdan tells people she makes clothes out of ground olives and onion peels, she gets more than a few raised eyebrows. “It’s definitely a conversation starter,” laughs the founder of Jordanian fashion house Studio BOR. An architectural engineer by training, Al-Rashdan began experimenting with

An architectural engineer by training, Al-Rashdan began experimenting with