R

Over the past decade, scientists and designers have increasingly recognized that the climate challenge is not only how we build, but what we build with. The construction industry is among the world’s largest polluters, and cement production alone accounts for roughly 8 percent of global carbon emissions.

In response, researchers worldwide are developing alternative building materials with lower environmental footprints—often based on recycled or locally abundant resources. One such innovation is now emerging from Israel: a building brick made largely from recycled Dead Sea salt.

Related: she makes pretty things out of Dead Sea crystals

Turning waste into raw material

Construction places an enormous burden on natural resources. According to the United Nations Environment Program, the sector consumes around 36 percent of global energy, contributes nearly 40 percent of CO₂ emissions, and is responsible for significant air and ecosystem pollution.

Israel, meanwhile, has limited natural construction resources. One of its most abundant materials is found at the Dead Sea, one of the world’s largest sources of industrial salt and potash. Each year, millions of tons of excess salt accumulate in evaporation ponds as a byproduct of mineral extraction. The buildup raises the lakebed, alters shorelines, and presents a long-term environmental challenge.

For decades, this surplus salt was treated as waste.

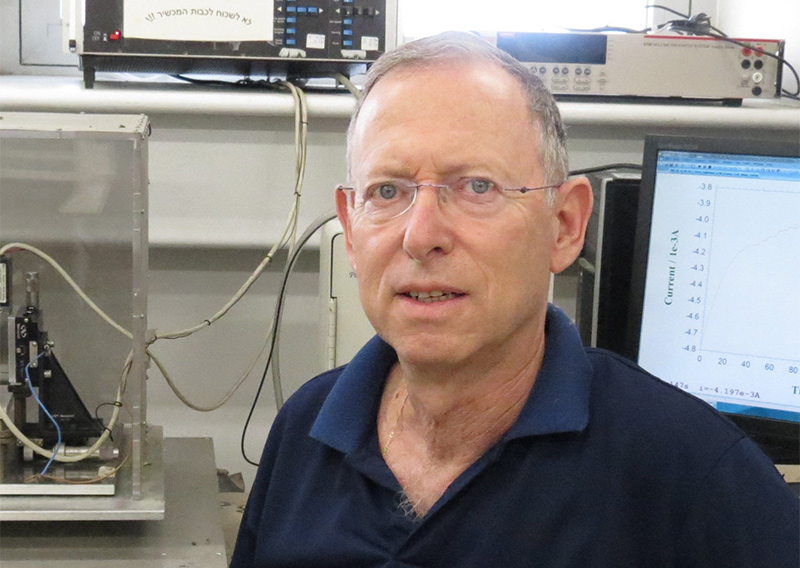

Since 2015, Danny Mendler, a professor in the Chemistry Department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been working to change that perception. His research treats Dead Sea salt not as a nuisance to be removed, but as a raw material that can be refined and reused.

Mendler developed a process that compresses salt with a small percentage of additional materials—around five percent—under high pressure to create solid bricks with strength approaching that of conventional concrete.

“If we can replace even a fraction of cement with salt, the environmental impact would be substantial,” Mendler explains. “Reducing cement use directly reduces carbon emissions.”

From chemistry lab to architectural design

In 2025, the research moved beyond the laboratory through a collaboration with architecture students at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology. As part of the Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning’s Studio 1:1 program, led by Michal Bleicher and Dan Price, students translated the material into a workable building system.

The group examined the physical qualities of salt—its mass, translucency, and structural behavior—and designed a prototype structure they called the Mediterranean Igloo. Through this process, they defined a standardized brick size of 8 × 8 × 24 centimeters, a 1:3 ratio that allows modular flexibility in construction.

The outcome was a uniform, scalable brick made primarily from Dead Sea salt—adaptable in shape, thickness, and surface texture, and compatible with contemporary building needs. Compared with conventional materials, the salt bricks offer a lower-pollution alternative while repurposing an existing environmental burden.

International recognition

The project was presented in October at Change: The Shape of Transformation, part of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Selected from 55 academic institutions worldwide, the Technion team was among just ten invited to exhibit.

The students transported physical salt bricks to Venice, drawing significant interest from architects and researchers. According to Bleicher, the response underscored growing global attention to material innovation in architecture.

“This is a material that is both natural and engineered,” she says. “Our next goal is to construct a full-scale structure in Israel using these bricks. We believe this approach can turn a serious environmental problem into a practical solution.”

What stands in the way

Despite its promise, widespread adoption is not imminent. The construction industry is notoriously conservative, and introducing new materials requires years of testing, certification, and regulatory approval.

“Every new building material must pass extensive strength, durability, and safety standards,” Bleicher notes. “That takes time, funding, and supportive regulation—which is often lacking.”

Still, the idea that decades of accumulated salt waste could become part of a cleaner construction future reflects a broader shift in environmental thinking: viewing crisis not only as a risk, but as a catalyst for innovation.

This article was prepared by Zavit, the news agency of the Israeli Society for Ecology and Environmental Sciences. It is republished with permission.