Unconfirmed photos are circulating on the internet that a Gazan family has started to rebuild their home using mud bricks. And just a few days ago we reported on a Saudi Arabian designer and his plans for using mud bricks as a solution to the refugee crisis.

Mud bricks are made from clay, sand, water and a natural binder such as rice husk or straw. They are dried in the sun—no firing, no fuel required at all. Properly made, they meet compressive strength and heat-conductivity requirements, act as fire-resistant and sound-insulating walls, and keep indoor temperatures relatively stable in both summer and winter. This works as long as there is a protective roof and the bricks are maintained. People in the past used to know how to do this but concrete made us forget ancient wisdom. If you travel to places like Ethiopia, most rural people are living in mud houses.

Related: ancient mud houses in the Muslim world

Globally, around 30 per cent of the world’s population still lives in earthen structures; the material is traditional across the Middle East, North Africa, India and much of the global South. The research community has moved well beyond nostalgia: recent studies on compressed earth blocks and fibre-reinforced mud bricks in places as varied as Australia, Togo and North Africa treat earth as a serious, testable low-carbon material, not as a second-best stopgap. Mud is flame-proof, readily available and as Hathan Fathy of the New Gourna Village argued can give people an honorable place to live.

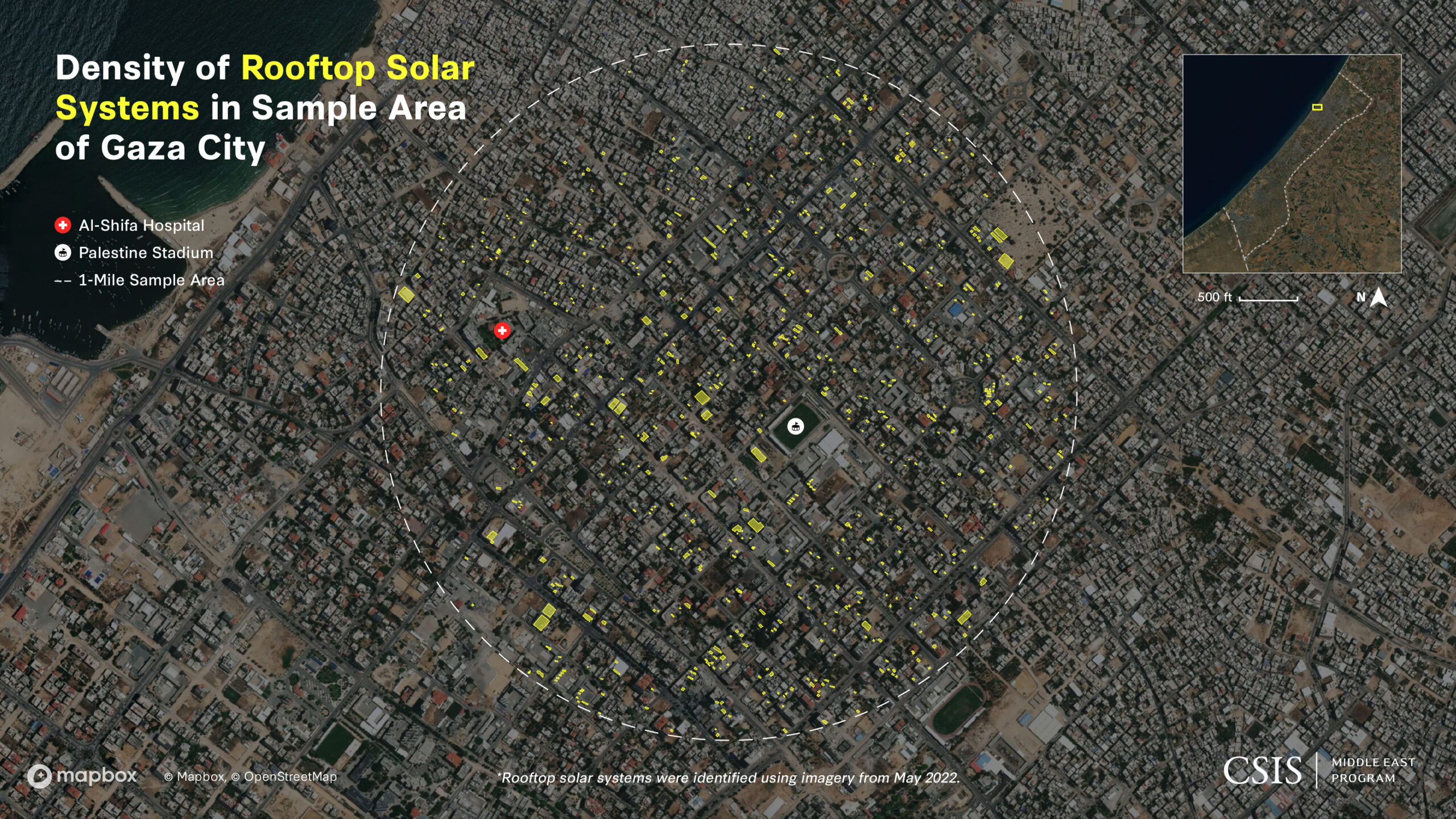

In Gaza, of course, energy and shelter are fused problems. Even before the current war, the territory never had enough grid power. Over roughly a decade, rooftop solar spread rapidly: one satellite analysis found at least 655 rooftop solar systems in a single square mile of Gaza City, and by 2022 the strip was estimated to have more than 12,000 such systems.

Solar became a genuine lifeline, keeping water pumps, small clinics, fridges and phones running when diesel ran out. See the map below of rooftop solar, which according to this source made Gaza the highest user per capita of solar rooftop energy in the world.

Much of that infrastructure has since been damaged or destroyed since Hamas started the war with Israel, but the lesson is still there in plain sight: when you give people robust, decentralised tools—sun and soil—they will use them to hold their lives together. Satellite-based damage assessments now show that a large share of solar installations have been hit, which only increases the urgency of planning low-carbon, distributed systems for any serious reconstruction.

For a practical NGO funder, this suggests a very grounded agenda that is neither experimental for its own sake nor romantic about “traditional” methods.

Gaza will need: field-tested earthen construction, training and demonstration yards that support local engineers, masons and women’s groups to run short, paid training programs in mud-brick and compressed earth construction. Small demonstration houses, clinics or community centers can double as real assets and training labs. Centers can also teach solar cooking and basic engineering skills.

Solar + earth “micro-campuses”: pair thick, thermally massive earthen buildings with rooftop or courtyard solar systems and simple DC micro-grids with small plots for farming and permaculture. Muslim women in Israel and the PA can travel to Gaza to give workshops on beekeeping (see Bees for Peace).

While Gaza has always been densely populated, new models in earthen building and rooftop gardens can enliven the hope for the next generation.