Sanctity in circularity? How Jewish history and sustainable practices meet in Greece today. Kos Island, Greece. The Kahal Shalom synagogue gets a sustainable remodel by Israeli-Greek architect Elias Messinas.

The word Ecology combines two Greek words: oikos (οίκος, meaning ‘house’ or ‘dwelling place’) and logos (λόγος, meaning ‘the study of’). It describes how biological systems remain diverse and productive over time. To achieve this, we need to keep materials in cycles of reuse, and reduce the need for new extractions and the production of waste.

Architect William McDonough and chemist Michael Braungart in their revolutionary book ‘Cradle-to-Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things’ (2002) present how to adopt a circular economy model through design and science. Their work and examples of circular practices in architecture and industry, are presented in the 2002 documentary film ‘The Next Industrial Revolution’ by directors Shelley Morhaim and Christopher Bedford.

The construction sector plays an important role in the economy. In Europe, it generates almost 10 % of GDP and provides 20 million jobs. It also requires vast amounts of resources, producing greenhouse gas emissions in material extraction, manufacturing, transportation and construction. It is estimated at 5-12% of total national greenhouse gas emissions. Here I write about the problem with deep sea mining for concrete.

In terms of waste, construction and demolition waste amount to about 35% of total waste generation, and about 50% of all extracted materials. In Europe, construction and demolition waste recycling is about 50%, although some EU countries recycle up to 90%. Circular economy in the EU is a growing sector with around 4 million jobs.

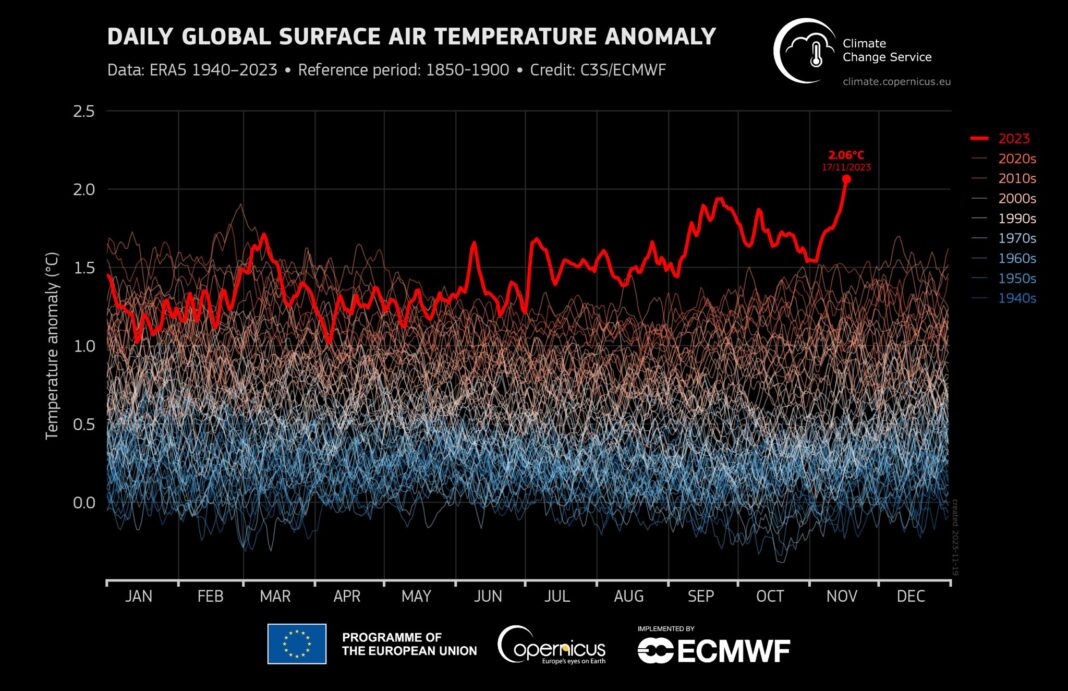

The EU – and the rest of the world – aiming towards 50% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, in order to reach the Paris commitment of keeping a global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels.

The construction sector requires bold moves by architects and designers to comply with this global goal. Not only towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions of producing new materials, but reducing waste production and illegal disposal of construction waste in nature, as well.

Circular practices – reuse of materials, reuse of construction waste, building materials disassembly, materials passport, urban mining for materials and others – are the way to go (see Rotterdam). Design for product and materials reuse and upcycling. To reach these ambitious goals one needs to start small and grow. Like the interior restoration project for the synagogue Kahal Shalom, on the island of Kos in the Aegean sea, in Greece. A small project aligning with a global ambition.

Inspired by leading architects on circular practices in Europe, such as Superuse studio and Rau Architects, this project explores the common ground between historic research, restoration and sanctity.

Applying Jewish laws in upcycling

According to Halakhah (Laws guiding Jewish life), based on the sanctity hierarchy of the Temple of Jerusalem, sanctity of a synagogue and its liturgical objects, requires upcycling. For example, a simple closet can be turned into an Aron Hakodesh, but not the opposite. Also, a simple desk can be turned into a Bimah. In a magical way, the reuse of these objects, based on a circular economy principle, raises their sanctity. These objects become at the same time more holy and the project more ecological. In other words, sanctity meet ecology on the Greek island of Kos.

The island of Kos is located in the Dodecanese complex in the eastern Aegean, near the coast of Turkey, near the island of Rhodes. It is known as the island of Hippocrates, the ‘father’ of medicine, who was born in Kos in 460 BCE. The island was under Italian rule from 1912 until 1943 and under German occupation between 1943 and 1945. In 1948, Kos and the Dodecanese, were incorporated to the Greek State.

In early 2022, with the increase of Israeli tourism on the island, the Municipality of Kos saw the need for a functioning synagogue to serve the growing demand for services and ceremonies. Until then, the alternative would be the nearby synagogue Kahal Shalom in Rhodes.

The synagogue Kahal Shalom in Kos, was designed in 1935 by Italian architects Armando Bernabiti and Rodolfo Petracco, and constructed by the Italian firm “De Martis-Sardelli”, in the Italian Colonial style. Kahal Shalom synagogue was erected after the previous synagogue of 1747 was destroyed in the earthquake of April 1933, which destroyed most of the island.

The Nazis made the Jews abandon their holy site

The synagogue functioned until the Nazis arrested, deported and annihilated the Jewish community in July 1944. After Liberation the synagogue was abandoned. In 1984 it was endangered with demolition. The Municipality, took a bold step and purchased the synagogue to preserve it as a cultural and exhibition hall. In 2022, in collaboration with the Central Board of Jewish Communities, a decision was made to restore the interior of the synagogue to serve, in a mixed-use, as a synagogue and a cultural center. Thus, serving tourists during the tourist and holiday season, and the local community during the rest of the year.

I am an architect and expert in the architecture, history, and restoration of Greek synagogues who undertook the restoration design and have been researching and documenting Greek synagogues for over 30 years. Since 2016, with my team of local expert architects, we have successfully restored the Monastirioton central synagogue and Yad LeZikaron synagogue in Thessaloniki (with KARD Architects D. Raidis and A. Kouloukouris), the Yavanim synagogue in Trikala (with Petros Koufopoulos), and are advancing the construction of a protective roof over the mosaic of an ancient Romaniote synagogue on the island of Aegina, dating from the 4th century CE (with engineer Argyris Chatzidis).

I also consult the Ministry of Culture in Greece, towards the enrichment of the official Archaeological Registry with more than 300 new entries of Jewish monuments and sites throughout Greece.

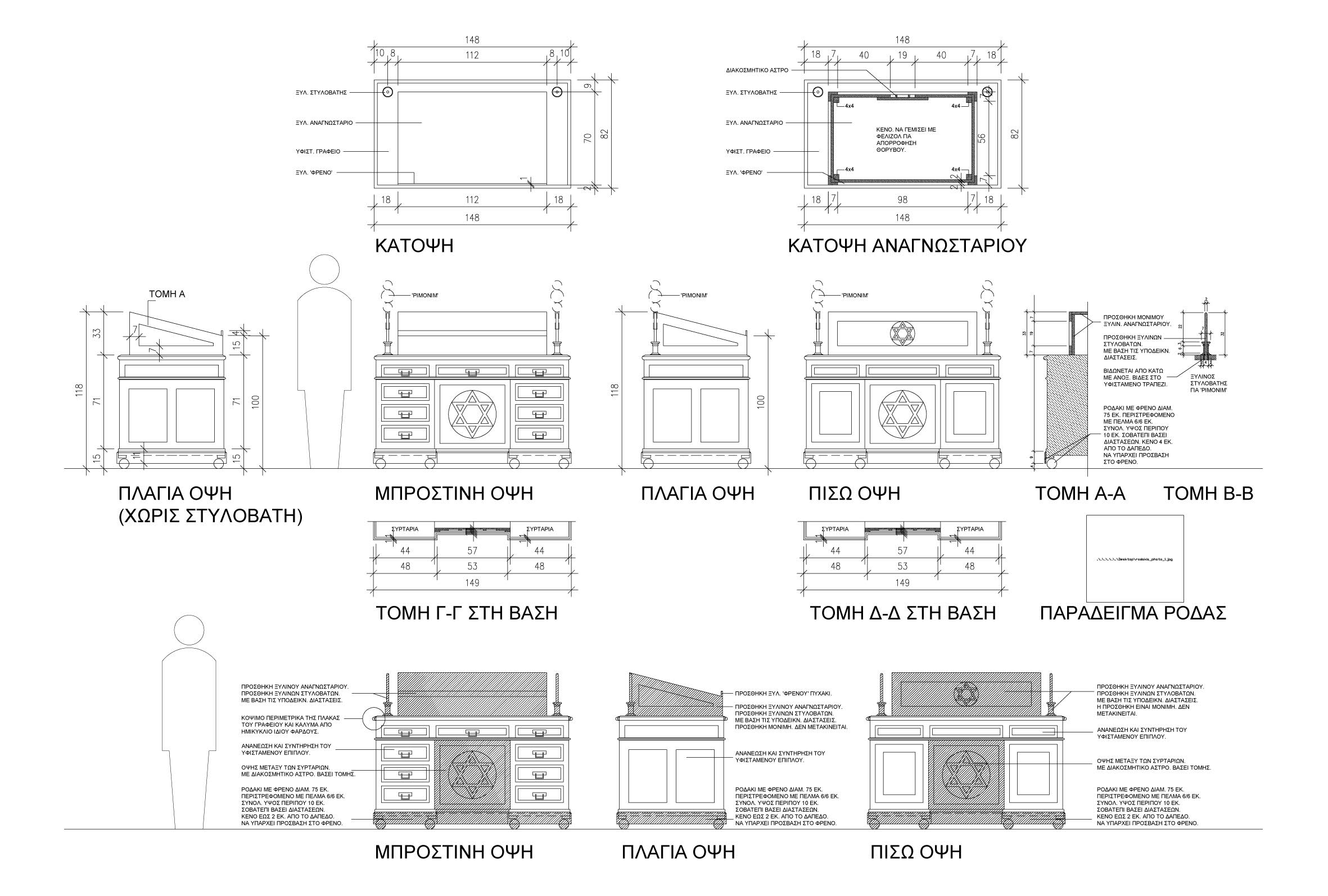

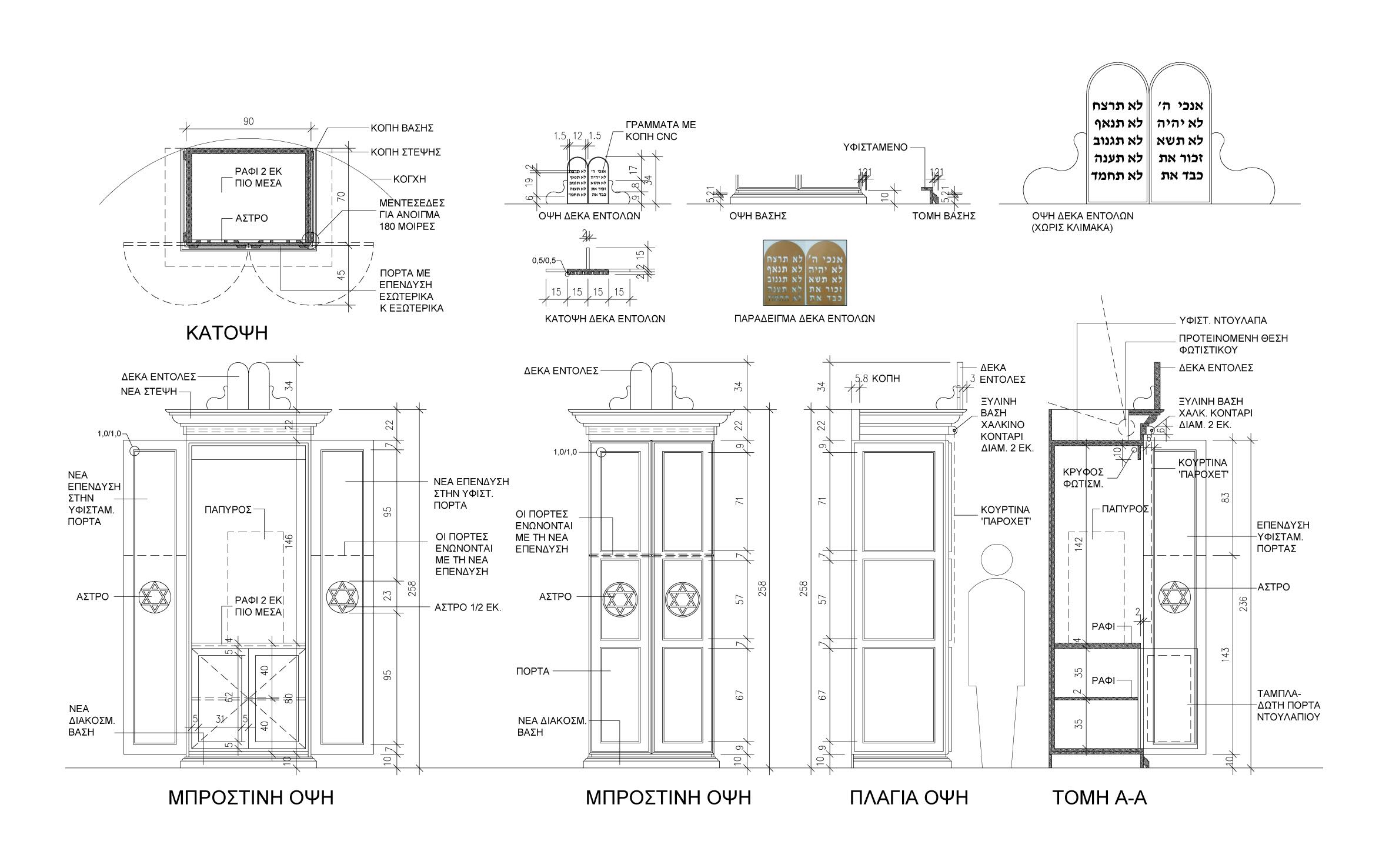

The restoration of the synagogue was based on research on Italian synagogues – including the Patras synagogue (1917) furnishings on display at the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens, and the synagogue Conegliano Veneto (1701) at the Museum of Italian Jewish Art in Jerusalem. The synagogue design was also based on circular practices, primarily, through the reuse of existing furniture as a way to raise their sanctity, and reduce waste in the process. In addition, the project was both more economical and faster to implement.

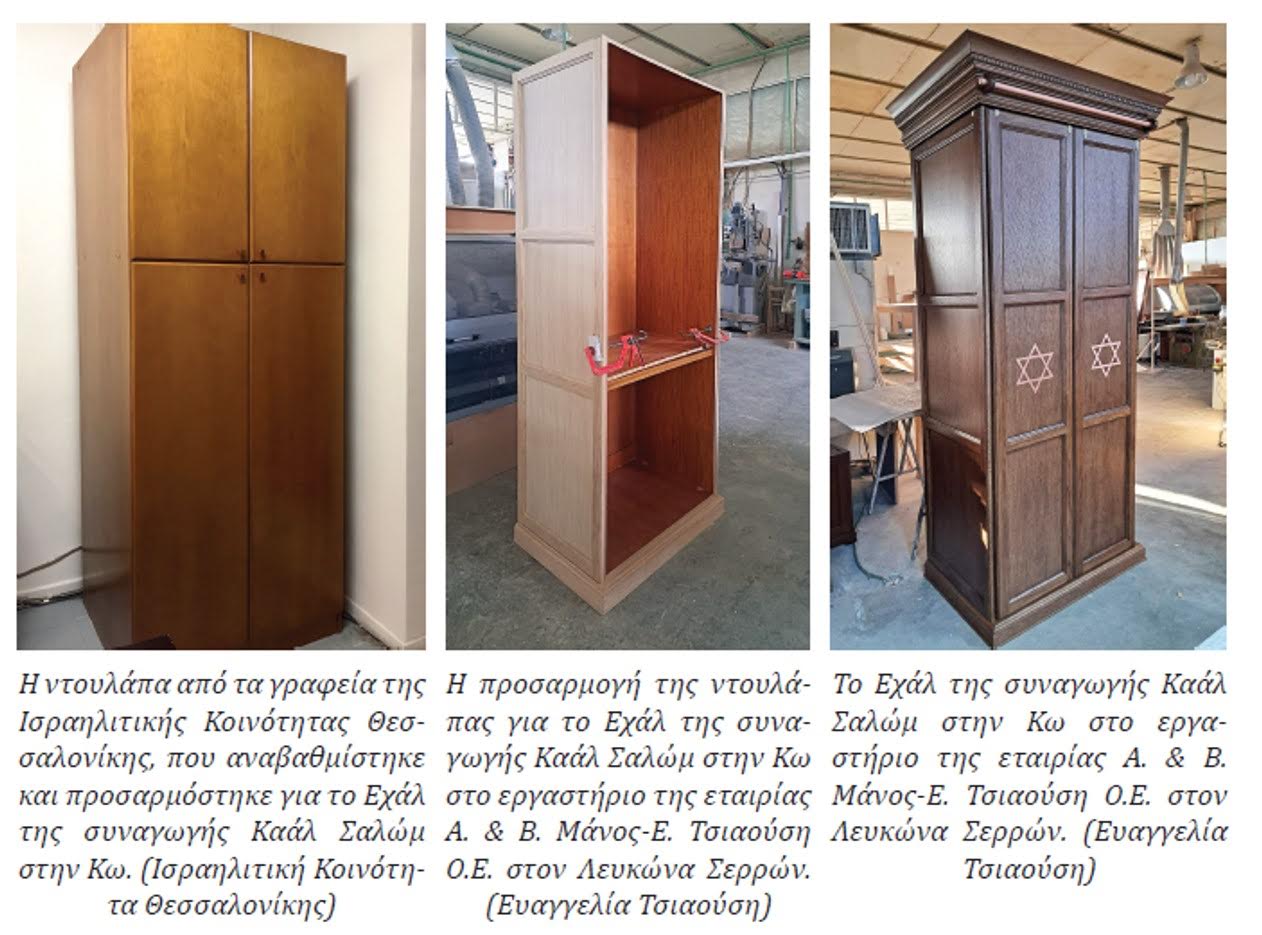

The design process in a nut shell: once the commission proceeded, the initial attempt of the architect was to order furniture from one of the synagogue furniture suppliers in Israel. As the furniture was produced in Ukraine, the Russian invasion made delivery schedules unpredictable. Further, the total cost was beyond the set budget. The architect then tried to find existing historic furniture to reuse from demolished synagogues in Greece, Turkey, Italy and the US. Once this option was exhausted unsuccessfully, the architect suggested using existing furniture: an office closet for the Aron Hakodesh and an old wooden office desk for the Bimah.

The furniture, originally in use and in storage at the offices of the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki, was recruited for the task. For the remodeling of existing furniture, the architect also consulted with the Chief Rabbi of Thessaloniki Aaron Israel, who confirmed the remodeling as Halahically acceptable as long as the sanctity of the furniture was upward: from regular furniture to synagogue sacred furniture, and not the opposite.

Based on detailed remodeling drawings, the carpenter Manos-Tsiaousi Co. based in Serres – NE of Thessaloniki, was chosen for the implementation. A local contractor undertook some light work to enhance the interior restoration. The work was completed in less than four months, and nearly half the cost of ordering new furniture. The synagogue was ready on time for the summer tourist season for the island, and was officially re-dedicated in July 2023.

Today, this small synagogue of 124 sq. m. sanctifies the circular practice of reusing existing furniture in the most profound way. It applies the principles of sustainability in a religious building, such as a synagogue, and as a result not only sanctifies the space and furnishings, but it also protects ecology and aligns human activity to the limitations of the planet, as well.

The synagogue Kahal Shalom is open for visits and services. NGO ‘Ippokratis’, whose offices are located in the former rabbi residence adjacent to the synagogue, can be contacted regarding upkeep and visit to the synagogue. The Greek book “Kahal Shalom: The synagogue of Kos” by Messinas was published on the occasion of the completion of the project, to fully present the history of the synagogue and the process of restoration. An English translation of the book is in preparation.

Link to Messinas, E. 2023. “Kahal Shalom: The synagogue of Kos”, Kos in Greek (links to PDF)

Author

Elias Messinas is a Yale-educated architect, urban planner and author, creator of ECOWEEK and Senior Lecturer at the Design Faculty of HIT, where he teaches sustainable design and coordinates the new SINCERE EU Horizon program, which aims to provide the tools for optimizing the carbon footprint and energy performance of cultural heritage buildings, by utilizing innovative, sustainable, and cost-effective restoration materials and practices, energy harvesting technologies, ICT tools and socially innovative approaches. . www.ecoama.com and www.ecoweek.org