More than a billion years ago, in a shallow basin in what is now northern Ontario, a subtropical lake—similar to today’s Death Valley—slowly evaporated under the sun’s gentle heat. As the water disappeared it left behind crystals of halite, or rock salt. The world back then was nothing like the one we know today. Bacteria dominated life on Earth. Red algae had only just appeared. Complex plants and animals would not evolve for another 800 million years.

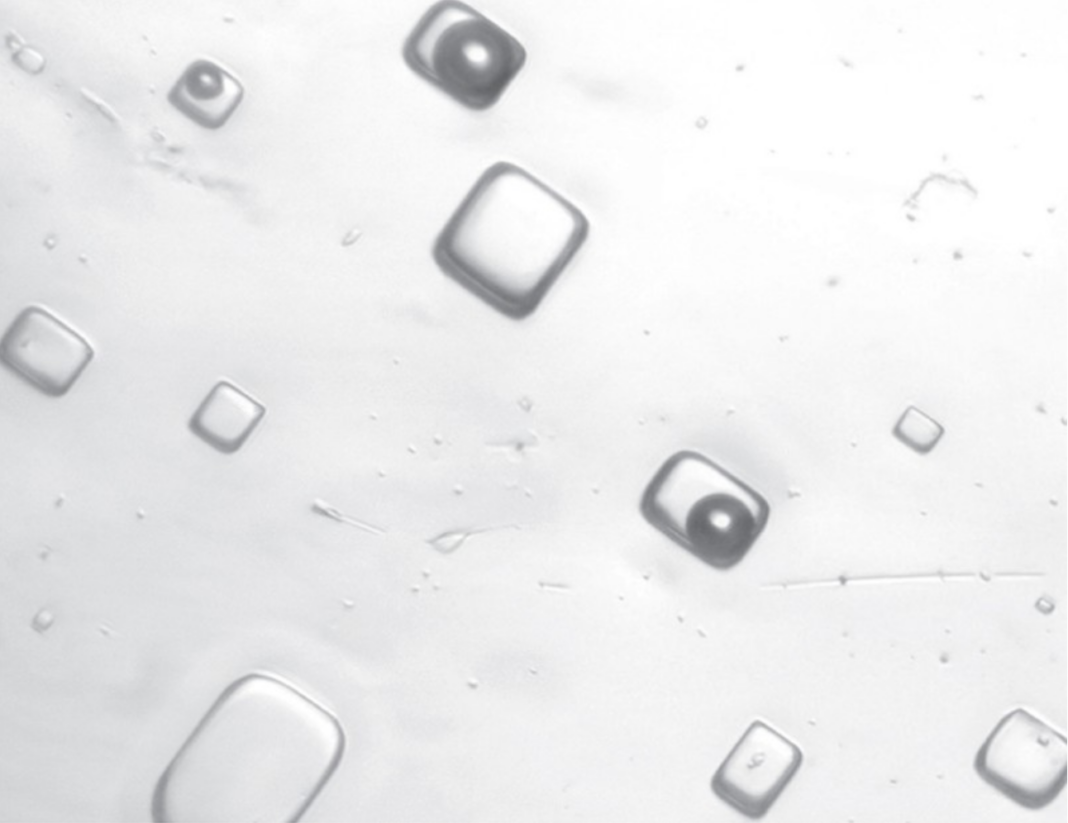

As the lake water concentrated into brine, tiny pockets of liquid and air became trapped inside the growing salt crystals. These microscopic bubbles were sealed off as the crystals were buried under layers of sediment, preserving samples of ancient air and water—unchanged for roughly 1.4 billion years. Until now.

Scientists have been able to analyze the gases and fluids locked inside these ancient salt crystals, effectively pushing our direct record of Earth’s atmosphere back by more than a billion years. By carefully separating air bubbles from the surrounding brine—no easy task—they were able to measure oxygen and carbon dioxide levels from a deep chapter of Earth’s past.

Opening these samples is like cracking open air that existed long before dinosaurs, before forests, before animals of any kind. As lead researcher Justin Park put it: “It’s an incredible feeling to crack open a sample of air that’s a billion years older than the dinosaurs.”

The results are striking. Oxygen levels during this period were about 3.7% of today’s atmosphere—surprisingly high, and theoretically enough to support complex animal life, even though such life would not appear until much later.

Related: Living water holds ancient memories in Ontario

Carbon dioxide levels, meanwhile, were about ten times higher than today. This would have helped warm the planet when the sun was much dimmer than it is now, creating a climate not unlike the modern one.

This raises a natural question: if there was enough oxygen to support complex life, why did it take so long for animals to evolve?

The answer may lie in timing. The sample represents only a brief snapshot of a vast stretch of Earth’s history—a period often nicknamed the “boring billion” because of its relative stability and slow evolutionary change. It’s possible the oxygen levels recorded reflect a temporary rise rather than a permanent shift.

“Despite its name, having direct observational data from this period is incredibly important because it helps us better understand how complex life arose on the planet, and how our atmosphere came to be what it is today,” Park said.

Still, having direct evidence from this era is invaluable. It helps scientists understand how Earth’s atmosphere developed and how conditions gradually became suitable for complex life.

Earlier estimates of carbon dioxide from this period suggested much lower levels, which conflicted with geological evidence showing there were no major ice ages at the time. These direct measurements, combined with temperature clues preserved in the salt itself, suggest a milder, more stable climate than previously assumed—perhaps surprisingly similar to today’s.

Notably, red algae emerged around this time and remain a major source of oxygen on Earth. The relatively elevated oxygen levels may reflect their growing presence and increasing biological complexity.

Far from being boring, this moment may represent a quiet but pivotal turning point—one that helped set the stage for the living world we know now.