We know about Chernobyl and Las Alamos: the lasting effects of radiation on the Saharan Tuareg in the desert

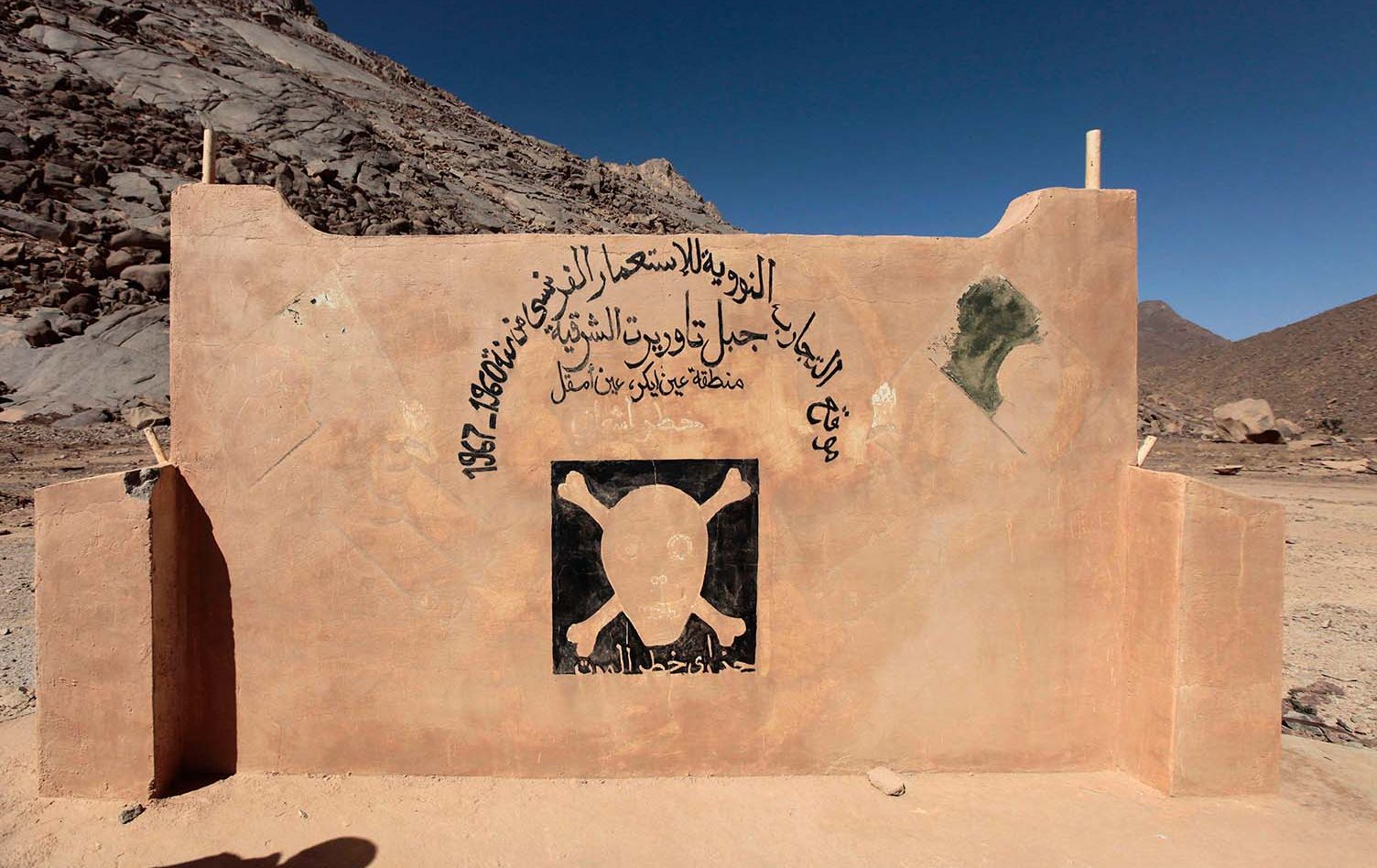

Between 1960 and 1966, seventeen nuclear detonations took place deep in Algeria’s Sahara Desert — first at Reggane and later in the Hoggar Mountains near In Ekker. Conducted under French supervision during the Cold War, these experiments were designed to develop a nuclear weapons capability. Their physical and political fallout is still with us.

The nuclear testing was not done in a vacuum and like at Las Alamos in New Mexico it affected the people nearby. In Algeria that was the Tuareg people. Others affected with the Berber-speaking nomadic group of the Sahara, whose territory spans large parts of southern Algeria; The Kel Ahaggar community which is a specific Tuareg confederation located in the Hoggar Mountains region off Algeria, and other local residents.

While less clearly documented in accessible sources, sites of the nuclear testing such as In Ekker and the surrounding desert zone indicate that French military, local manual workers, nomadic pastoralists, and their settlement communities were exposed.

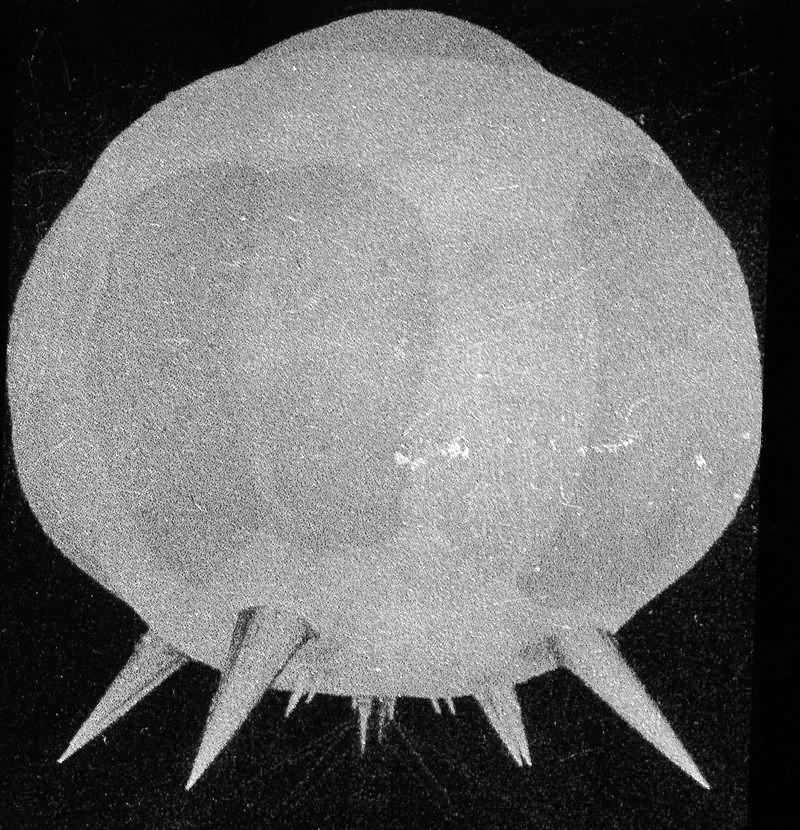

A peer-reviewed study in Applied Radiation and Isotopes found measurable levels of plutonium and other radionuclides remaining at former test sites decades after the final detonation. A broader review of global weapons tests published in Environmental Sciences Europe confirms that radioactive contamination from Sahara tests persists in soils and fractured rock and can be re-mobilized by desert winds. If England gets locusts blown to its shores from Egypt, imagine how far radioactive dust can travel.

Algeria declared independence from France in 1962, but the Évian Accords that ended open conflict also granted France continued access to certain military and research sites in the Sahara for up to five years after independence. These terms were negotiated between the French state and Algeria’s provisional government (the FLN leadership at the time). This means the testing program after 1962 did not happen in a legal vacuum: it was authorized in writing by the Algerian Government, and it served strategic interests on both sides at the time. There was a power imbalance, giving the Algerians not much choice.

For France, the Sahara was a proving ground for weapons credibility as the Americans did in the deserts around the Los Alamos nuclear testing facility, established in 1943 as Project Y, a top-secret site for designing nuclear weapons under the Manhattan Project during World War II. For Algeria’s new leadership, the agreement helped secure full political recognition, state continuity, and material support at a fragile moment of transition to their autonomy. The cost of that compromise was largely borne by remote southern communities, as is the case in many of today’s superpowers.

Some of the underground nuclear shots tested at In Ekker were supposed to be fully contained. In reality, not all of them were. One detonation, known as the Béryl Incident (1 May 1962), vented radioactive dust and hot debris into the open air when the test tunnel’s seal failed. French military personnel, engineers, and nearby residents were all exposed –– some highly contaminated. Decades later, radiation dose reconstructions and site surveys continue to document contamination in the blast zones and surrounding scrap fields.

People living downwind describe long-term health problems, loss of grazing land, restrictions around traditional water sources, and the normalization of sickness with no official acknowledgment. The same which happend in Love Canada, USA, a site I visited in the 90s. This happens in Turkey today where the government fails to recognize cancer clusters in industrialized zones outside the city. One scientist we interviewed was threatened to be put in jail if he continued his scientific research on the issue.

French veterans of the Sahara tests have in some cases received recognition and partial compensation under later French law, while Algerian civilians have struggled to access comparable review or support. Algeria, like most countries in North Africa and the Middle East are about 30 to 40 years behind on environmental issues and research. It’s not so easy to point a finger and find a villain. Algeria, 65 years on does not have a great environmental record.

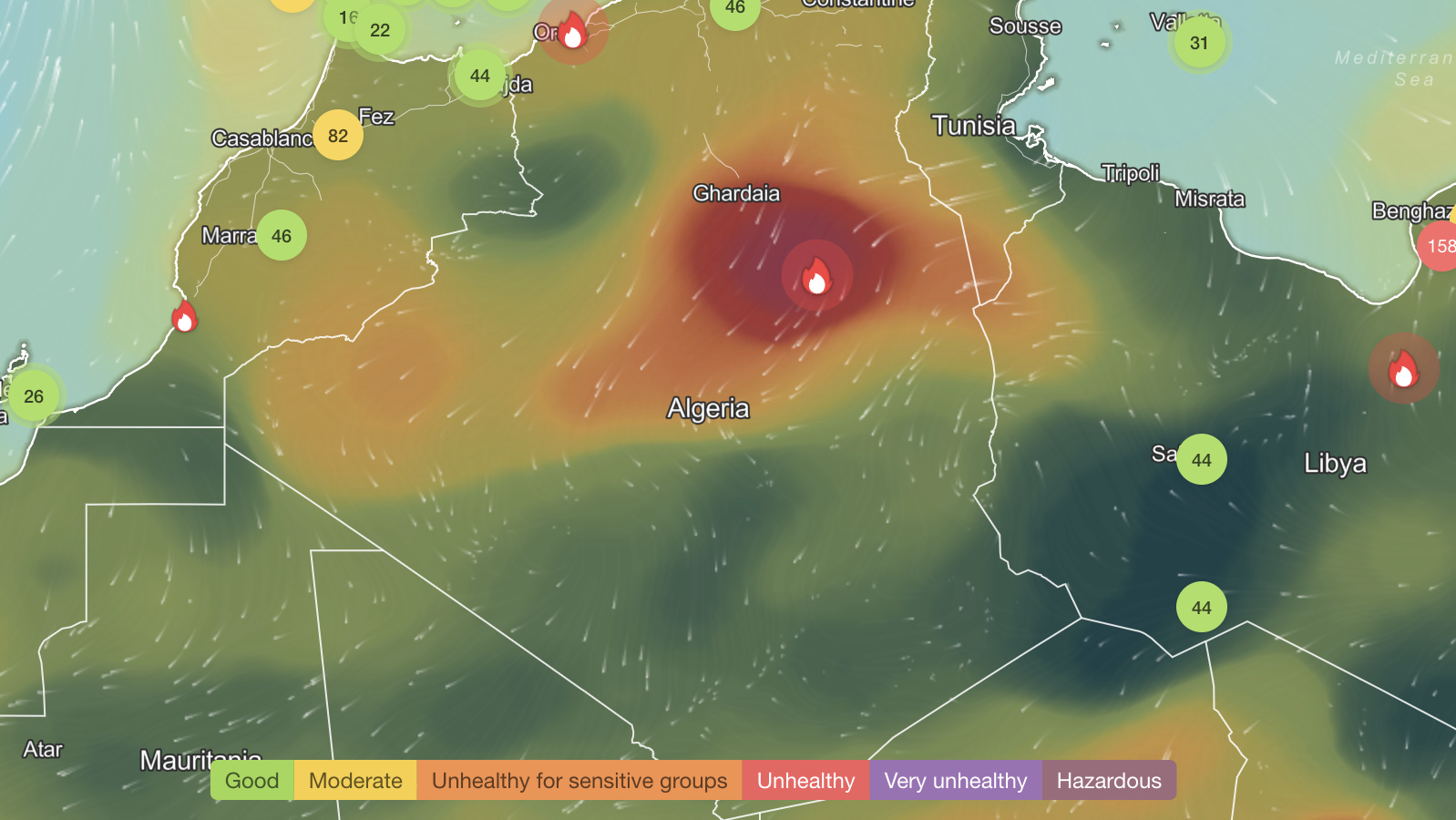

Algeria faces a complex mix of environmental and pollution challenges that extend from its Mediterranean coast to its Saharan interior. The most pressing issue is air pollution in major cities such as Algiers, Oran, and Constantine, where outdated vehicles, industrial emissions, and open waste burning raise fine particulate (PM2.5) levels to more than three times the World Health Organization’s recommended limit.

Water contamination is another critical concern. Much of Algeria’s wastewater is released untreated into rivers and the sea, carrying agricultural runoff, heavy metals, and plastic debris. Coastal zones near industrial centers like Skikda and Annaba are among the most polluted in the southern Mediterranean, threatening fisheries and tourism. Groundwater in rural regions also suffers from nitrate and pesticide infiltration.

Inland, desertification and soil erosion are advancing due to overgrazing, deforestation, and a warming climate. The country loses thousands of hectares of forest annually to drought and wildfires, despite new reforestation and water-retention projects.

Finally, oil and gas extraction along with urban waste management gaps add to Algeria’s pollution load. While national plans now emphasize renewable energy, afforestation, and stricter environmental monitoring, progress remains uneven. The challenge is balancing economic growth with sustainable resource stewardship. With an estimated 2,400 billion cubic metres of proven conventional natural gas reserves, Algeria ranks 10th globally and first in Africa. It also has the third largest untapped unconventional gas resources in the world.

Algeria has 12.2 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, ranking it 15th in the world and third in Africa. Currently, all oil and gas reserves are located on land and it is a major contributor to oil pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. Algeria is exploring new possibilities for oil and gas extraction, including offshore and shale gas opportunities.

The legacy of Sahara nuclear testing is often framed as a simple one-direction story, but the reality is more entangled. France designed, managed, and detonated the devices. Oversight after 1966 has involved both governments and, at times, international agencies. What has not happened at scale is transparent, long-term medical screening for affected communities and a full clean-up of contaminated waste that was left in place.

But putting it in scale, Algeria has a lot of environmental accounting to do. Just blaming France or “colonial” powers is short-sighted and distracting, absolving locals from trying to better on its own locally-made problems due to extremely high levels of corruption. At Green Prophet we zoom out and try to show you the wider story to issues that affect every human on this planet.

Want to learn more about the environment in Algeria? Start here:

This stunning ancient citadel in the Sahara Desert has a mysterious past

How Islamic-era agriculture points way to sustainable farming methods

Algerian Judoka expected to defeat an Israeli player before match

Algeria’s Controversial Love Lock Bridge Rebrands Suicide

Aerodynamic ARPT Headquarters Diverts Algiers’ Hot Desert Winds Naturally

Oil fracking protestors in Algeria rise up against their regime, Total and Shell

Algeria to Invest $20 billion USD in renewable energy

Top wildlife destinations in North Africa (includes Algeria)