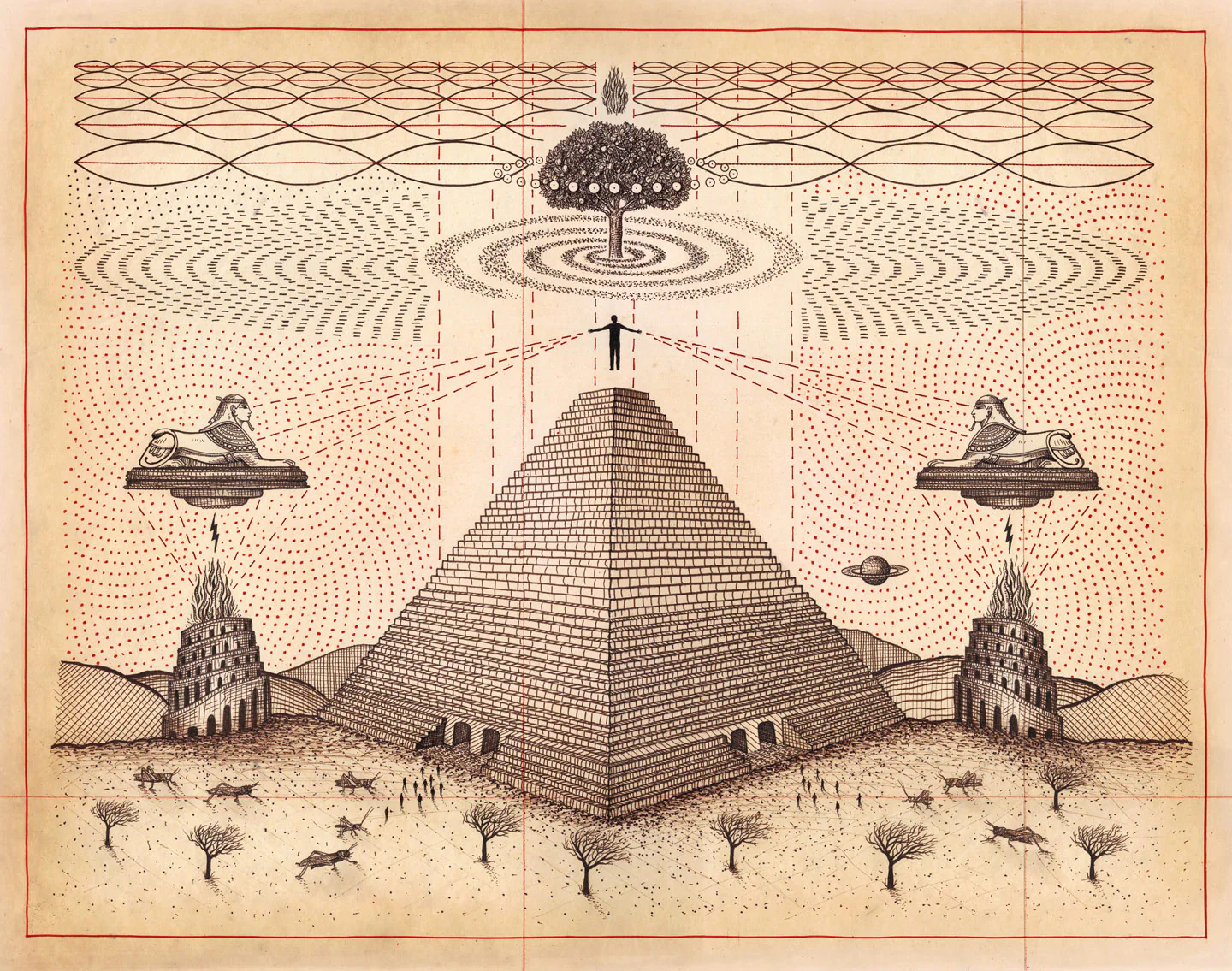

In Islamic tradition, there is a point where creation ends — a boundary at the 7th heaven that marks the limit of what any created being can reach. That boundary is called Sidrat al-Muntahā, translated as the Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary.

The reference appears in the Qur’an in a short, concentrated passage in Surah An-Najm (The Star), describing a vision “at the Lote Tree of the most extreme limit.” The lote tree is known as the Sidr tree, from which the Yemenites make holy honey, and it is also believed to be the thorn worn by Jesus.

Where the lote shows up in Islam’s most famous ascent story

The boundary, or Sidrat al-Muntahā is most often discussed in connection with the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey and Ascension (al-Isrā’ wal-Mi‘rāj) to Jerusalem, which was a dream. For in reality, Mohammed never actually made it to Jerusalem, the Holy City. In a well-known narration recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari, the moment is described with a modest line:

Then Jibril took me till we reached Sidrat-ul-Muntaha … which was shrouded in colors indescribable.

In the same narration, the ascent is tied to the establishment of the five daily prayers — a reminder that the story returns to lived practice. In Judaism, the three-times daily supplication was inspired by the Jewish forefather Abraham, described as “standing” before God, interpreted as the first morning prayer (Genesis 19:27), and Isaac going out to “meditate” (or pray) in the fields and Jacob inspired by the evening prayers.

What “utmost boundary” means

In Islam, the Arabic name is descriptive: sidrah (transliterated with an h or without) refers to a lote tree, and muntahā means the farthest point or extremity — the tree at the limit. One academic treatment explores how “the lote tree of the boundary” functions as a threshold image in Islamic interpretive traditions.

Knowing about the concept of the Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary helps explain a core idea in Islam: God is beyond creation, and there are limits to what humans — and even angels — can know. Islam doesn’t aim for union with God or endless revelation; it emphasizes humility, restraint, and knowing when to stop asking. The story of the Lote Tree shows why Islam values discipline and practice, like daily prayer, over personal mystical experience. Protecting the boundary between the divine and the human is seen not as restrictive, but as essential.

The sidr tree and the Lote Tree

The sidr tree is a real, familiar tree across Arabia and parts of the Middle East. And it makes great honey. In English it’s often called the lote tree or Christ’s thorn jujube (Ziziphus species). It grows in harsh, dry conditions, provides deep shade, edible fruit, and medicinal leaves, and is known for its resilience.

For centuries it has been part of everyday desert life — practical, tough, and unremarkable in appearance.

In Islam, this ordinary tree is given extraordinary meaning. Sidrat al-Muntahā — the Lote Tree of the Utmost Boundary — takes its name from the sidr tree but is not simply a botanical reference. It marks the furthest limit of creation and knowledge, the point beyond which no created being, including angels, can go.

The Qur’an mentions it briefly, without description or symbolism piled on. That restraint is intentional. Islam does not turn the sidr tree into a symbol of God or a ladder toward divinity as the Jewish text goes – Jacob wrestling with the angel. Instead, it uses a known, grounded tree to mark a boundary. In Islam God remains beyond the created world, and knowing where that boundary lies is part of the faith.