An Analytical Report on the TEDxOmid Architecture Event Titled “Narratives of Responsive Architecture” in Tehran, Iran

On the 10th of Mehr 1404 (corresponding to October 1, 2025), coinciding with the commemoration of World Architecture Day in Iran, the TEDxOmid Architecture event was held. Licensed under the official licence of the international TED organization, this program was designed to promote contemporary architectural perspectives, sustainable development, and the social responsibility of architects.

The event is notable from two aspects; first, its connection to the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025 lies in adopting a critical, forward‐looking, and transdisciplinary approach as a platform for dialogue and experimentation with environmental, technological, and social strategies, reflecting the Biennale’s mission to address global challenges through multidisciplinary collaboration and adaptive design philosophies.

And second, the method of selecting the speakers and their performance, who were ostensibly introduced as bearers of responsive and people-centric ideas. However, a closer examination of their lecture content and professional resumes reveals signs of a significant gap between the proclaimed slogans and their actual practice.

According to the official statement, the program was held to review and present innovative solutions by architects for major environmental and social challenges such as environmental degradation, inequality, injustice, class disparity, the human share of the city and green spaces, and to create a world that cherishes life and flourishing over mere existence. The declared goal was to demonstrate that architecture can respond to these challenges and play its part in reproducing social justice and ecological balance.

Like we learn at the Hormuz super-adobe island project and its greenwashing celebration by Aga Khan, global organizations are not doing due diligence on partners and projects they represent.

The composition of the speakers at the TED event indicates that they have played effective roles within Iran in reproducing urban injustices and exacerbating environmental problems such as water and air pollution, or at the very least, their professional resumes have largely shown little transparency, both in theory and practice, regarding responsible commitments. This contradiction between the announced slogans and the actual backgrounds of the speakers is the central axis of analysis in this Green Prophet exclusive report, which will be examined in detail.

The TED charter and criteria emphasize a deep commitment to environmental sensitivities and scientific standards. It is expected that speakers, in addition to having innovative ideas, possess scientific and practical backgrounds in their professional fields. This part of TED’s principles specifies that talks must be based on well-founded and verifiable findings, and that unscientific claims or unsustainable development activities have no place.

While the TED speaker selection process is conducted with high precision and scientific and professional reviews, unfortunately, in events like TEDxOmid Architecture in Iran, most of the participating speakers have had weak scientific and practical achievements in specialized fields such as responsive architecture and sustainable development. Their backgrounds are more focused on unsustainable development activities.

Theme: Narratives of Responsive Architecture

Speakers: Mohammad Majidi, Reza Daneshmir, Shadi Azizi …

Curator: Mehrdad Zmohammadi

Designer: Aida Alibakhsh

Source: Instagram @tedxomid

On the other hand, in international arenas, projects and programs like Countdown, in collaboration with scientists, policymakers, and environmental activists, carry out coherent and scientific activities to combat the climate crisis, and in‐depth, specialized discussions on major urban and social topics like gentrification are held, featuring speakers with outstanding resumes in sustainable development.

This contrast shows that strict adherence to scientific and ethical frameworks and criteria in selecting speakers is key to maintaining the credibility and impact of TED-related events. Therefore, critiquing the TEDxOmid Architecture event can be based on these very frameworks to demonstrate how the mismatch between the speakers and TED principles has negative consequences for the scientific and social integrity of the event.

This complicates the correct path towards achieving a bright future and sustainable development for Iran and simultaneously diminishes public trust in the accuracy and honesty with which issues are expressed; while Iran deeply needs a foundation for public trust-building so that people and society can move in sync with these essential approaches.

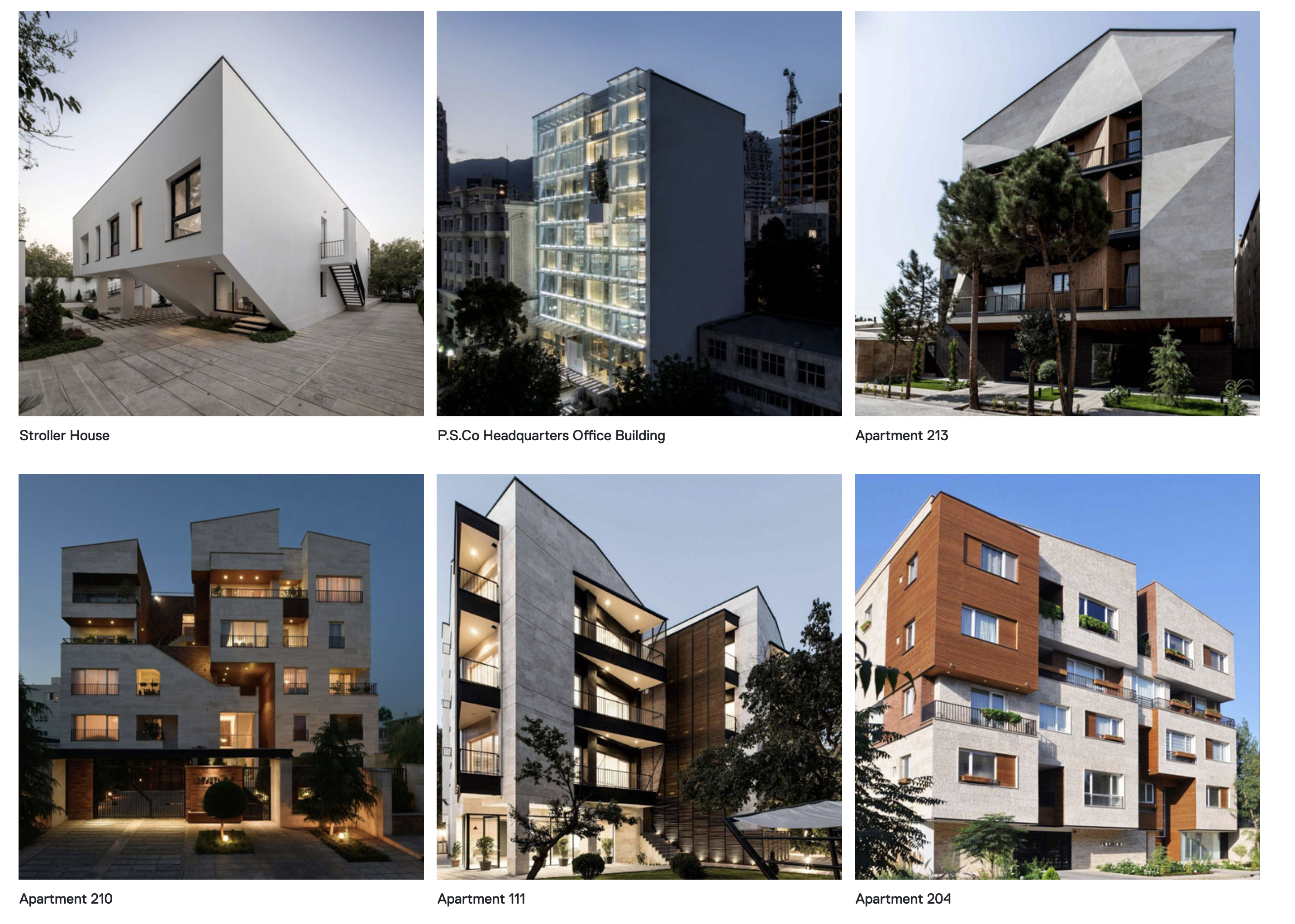

An overview of the speakers can be assessed based on two criteria: one through their articles and research efforts, and the other through architectural and urban projects, which can be obtained by referring to each speaker-architect’s personal website: Bonsar, TMA, Nesha.

In her talk, Shadi Azizi asks (translated from Parsi):

Can Vitruvius’s three fundamental principles of architecture — stability, beauty, and utility — be redefined, and can the responsiveness of architectural action in today’s era be interpreted beyond these three concepts, in a more complete, precise, and updated way? What are architects’ solutions to issues such as environmental destruction, inequality and injustice, class divides, and humanity’s share of the city and green spaces — for a world that values living and flourishing, not merely existing? How does socially conscious design, as the architect’s social responsibility for the common good, find expression within the discipline of architecture? The format of the presentation is a narrative — an endless narrative with an open ending that may not be entirely clear. It is situational, in a state of becoming, and includes an invitation for all architects to participate.

Considering the status of the projects, especially in Tehran, it becomes clear that many of the speakers are among the most prominent brand architects in the field of commercial towers, banks, and mall developers. In contrast, social and environmental projects are either non-existent or very faint, often executed on a commissioned and short-term basis according to the demands of government bodies and large financial institutions.

This focus primarily on tower and commercial projects, created without regard for the real needs of society and serving more as displays of power for banks and powerful institutions, indicates a major void in contemporary architectural approaches. Such a trend not only limits the research and scientific value of the speakers but also has widespread negative consequences for sustainable urban development, social justice, and public trust. If scientific and social approaches are not considered in the selection of speakers and projects, the risk of diluting the primary mission of education, impact, and social responsibility in architectural events increases.

In Iran, there is practically no integrated and transparent reporting on the sustainability and environmental indicators of projects, whereas in Europe, such reports and standard certifications are mandatory, even for small projects. For example, large residential or commercial projects in European countries cannot obtain construction permits without acquiring certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). LEED is an international standard that assesses the sustainable performance of buildings in areas such as energy consumption, water resource use, indoor air quality, material selection, and waste management, granting official certification to projects complying with these principles.

On a larger urban scale, projects like King’s Cross Central in London are examples of sustainable urban regeneration and development, where all its phases have been assessed against LEED and BREEAM standards, and environmental indicators, energy consumption, and the quality of life for residents and space users are continuously monitored.

For this reason, the companies founded by these architects lack any official confirmation of adherence to even the basic principles of sustainability and environmental standards, while in Europe, compliance with such standards is considered a prerequisite for professional activity and a sign of credible, sustainable architecture and urban development.

On the other hand, in the academic and scientific context, experts and researchers agree that high-rise construction without targeted placement in Tehran has altered the urban wind flow and, by blocking natural wind corridors, negatively impacts air ventilation. This leads to the accumulation and increased concentration of pollutants and exacerbates air pollution.

Specifically, permits for high‐rise construction in sensitive areas like District 1 of Tehran, which is the main route for north-to‐south winds, have blocked this natural wind channel and caused extensive environmental damage. The sale of density permits and the construction of tall towers have reduced wind flow at the city level, and during temperature inversion in winter, pollutants are trapped in the surface air, increasing pollution.

Studies from the University of Tehran and the research institute of the country’s Meteorological Organization, as well as reports from the Supreme Council of Urban Planning and Architecture, confirm these impacts and state that high-rise buildings in the city’s air corridors, by reducing wind speed, cause “air stagnation” and the accumulation of pollutant particles. Thus, high-rise construction indirectly plays a role in increasing Tehran’s air pollution, although some city managers have denied this effect, but scientific studies and official reports emphasize it.

Until now, little attention has been paid to the importance of architecture and construction—whether beautiful or incongruous—and to what extent architecture and building can have a destructive impact on climate change and be considered a factor of environmental risk.

Climate change is not spontaneous and passive –– rather, it is the result of limitless exploitation of nature and unbridled construction based on a lack of adaptation to fundamental contextual needs, which occurs gradually. This process is like a silent and even misleading death, where today in Isfahan, Tehran, and Mazandaran we clearly face terrifying news such as land subsidence, severe air pollution, etc.

Climate change is a serious threat to Iran and, on a larger scale, to the planet Earth, but the dangerous part is thinking that this phenomenon is limited to one province or region and cannot, for example, cause severe and similar crises in Gilan as in Isfahan and Tehran.

Urban and even rural construction patterns have so far been accompanied by a serious restriction of groundwater arteries, which can be reached even with a two‐meter excavation. It must be understood that based on soil type and these underground aquifers, Gilan is considered a sensitive habitat, and this team and this type of development outlook, lacking scientific, academic, and practical backing, can never offer a bright prospect for this region.

The People?

Who are the “people” and what is called “architecture”? A question that seems simple on the surface, but at its core challenges the boundaries between life, society, and form. Today’s understanding of architecture, especially within the global academic sphere, is transitioning from mere aesthetics towards a concept referred to as “architectures of care” and Responsive Architecture. It should be an approach that asks:

Who is this project for?

What impact does it have on the environment and society?

And how much environmental, social, and financial resources does it consume or revitalise?

In such a perspective, the social and environmental critique of Iranian architecture is an exploration along this very path, but within a cultural context that acts more resistantly and complexly towards change.

The Position of Iranian Architecture in Facing Change

The fundamental question is where Iranian architecture stands today and in which direction it is moving. While global architectural discourse has moved towards concepts such as livability, resilience, spatial justice, and cultural sustainability, the space of Iranian architecture remains largely stagnated in aesthetic and formal layers.

This situation has several key characteristics:

Architectural criticism is often limited to formal and superficial judgments;

Key concepts related to environment and society remain at the theoretical stage and have not found practical translation; And the professional community shows defensive and sometimes denialist behaviour towards social critique. This gap between global discourse and local reality has placed Iranian architecture in a state of transition; a situation where neither has the past paradigm been completely abandoned, nor has the new horizon been clearly established.

The Prospect of Transformation in Iranian Architecture

On a global scale, the concept of “architecture of care” and responsive architecture is gradually becoming one of the fundamental values of contemporary architecture.

In Iran, scattered signs of this change are emerging: Projects that show attention to everyday life, local context, and social capacities. But they have not yet reached the level of a pervasive and structural discourse. However, given the historical background and civilisation of the Iranian plateau, one can hope that achieving it is not out of reach. In this framework, eco-centric and social architecture strives to re-establish the connection between environment, society, and form.

Research in this field is based on co-existence; a search for achieving a multidimensional understanding of society and everyday life, and a way to recognise the invisible layers of collective life.

What is taking shape on this path is a new chapter of thought and research in Iranian architecture; a chapter whose progress relies on strategic management, a gradual understanding of context, and reflection on minute and hidden details. Elements whose meaning and impact are revealed only over time, and the establishment of correct laws and definition of standards will shape a more sustainable path for the foundation of Iran’s future architecture.

Perhaps for this context, which has distanced itself from its natural, cultural, and social grounds over several decades, the fundamental question is how can Iranian architecture be conceived? Architecture in such conditions must be re-read not merely as a physical form, but as a system of meaning, life, and collective reflection, and its examples should involve trust-building within a society that itself has been pioneering and has a brilliant resume.

The new generations today well know that the environment, as the context of architecture, is no longer a secondary or decorative subject; rather, it is the foundation that defines the very possibility of architecture’s continuity. If we consider architecture the language of the relationship between humans and the earth, then disconnection from the local environment is, in fact, a disconnection from meaning. Therefore, rethinking Iranian architecture inevitably involves returning to this fundamental connection between land, society, and form—a connection that finds meaning not at the level of imitating past indigenous patterns, but in the conscious reproduction of livable and contemporary values.

But another question is, where lies the boundary of architecture’s efficacy? Is architecture only effective to the extent that it responds to physical needs, or does it gain meaning when it can form a system of care, coexistence, and environmental reproduction, and consider its impact on a larger geography? And ultimately, who can be the narrator?

––––

Ronak Roshan Gilvaei Architect & Researcher | Sustainable Design, Architectural Restoration & Urban Renewal, based in Iran. The author reached out to TED organizers and there was no comment.