In a surprising crossover between neuroscience and marine biology, researchers have shown that octopuses can fall for the “rubber arm” illusion—a trick long used in human studies to explore how the brain integrates sight, touch, and proprioception (our internal sense of body position).

Related: is keeping a pet octopus cruel?

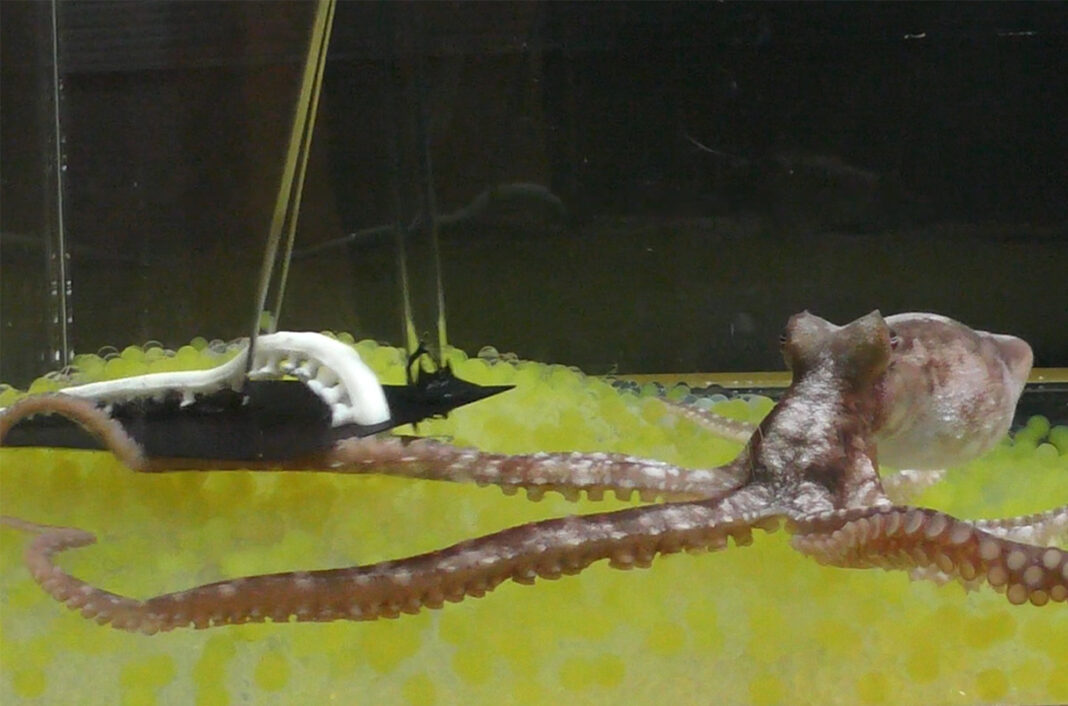

The team, led by scientists studying the plain-body octopus (Callistoctopus aspilosomatis), crafted a realistic fake arm and gently pinched it while simultaneously stimulating the real limb—just as psychologists do in human tests. The octopus responded to the fake touch as if it were its own, demonstrating a form of body ownership never before confirmed in invertebrates.

The researchers suggest the octopus displays a “primitive form of bodily self-consciousness,” indicating a potential shared basis for body ownership perception across very different species.

The implications are profound—not just for understanding intelligence, but for rethinking our relationship with non-human minds. Octopuses have long fascinated scientists for their problem-solving skills, tool use, and complex behaviors. Now, this illusion-based test reveals they may also share a self-body awareness once thought to be uniquely mammalian. Should we be eating them?

From a sustainability standpoint, this study feeds into a growing conversation around how we value marine life and intelligence in environmental policy. If octopuses exhibit this level of sentient processing, how should that affect the way we fish, farm, or conserve them?

As we develop more empathetic frameworks for environmental stewardship, understanding the inner lives of other species—especially one as cognitively complex as the octopus—may be key to designing more ethical, intelligent, and sustainable systems.

The study revealing that octopuses can experience the “rubber arm” illusion was led by Sumire Kawashima and Yuzuru Ikeda at the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa, Japan. They tested six plain-body octopuses (Callistoctopus aspilosomatis) and found that when the fake and real arms were stroked simultaneously, the animals responded defensively to a pinch on the fake arm—evidence of body-ownership perception in octopuses.