Biomimicry looks to nature for helping us engineer human products such as vernacular design

For years, scientists believed the exceptional fertility of tropical Ferralsols—a crumbly, porous soil found in regions like the Brazilian Cerrado and parts of West Africa—was simply the result of mineral weathering. But new research has cracked open that theory, revealing a hidden network of co-engineers: termites and ants. These social insects have not just inhabited these soils—they’ve built them.

In a landmark perspective published in Pedosphere Dr. Ary Bruand and colleagues at France’s Institut des Sciences de la Terre d’Orléans trace how millions of generations of termites and ants have sculpted the structure of Ferralsols. By transporting minerals from deep underground and engineering an intricate system of tunnels, these insects have created the porous, breathable soils that support some of the world’s richest tropical biodiversity and agriculture.

“This is like discovering that the pyramids weren’t built by natural erosion, but by ancient engineers,” said Bruand. “These insects have been performing ecosystem services worth billions of dollars, completely unnoticed. Their soil structures are more sophisticated than anything we’ve designed in labs.”

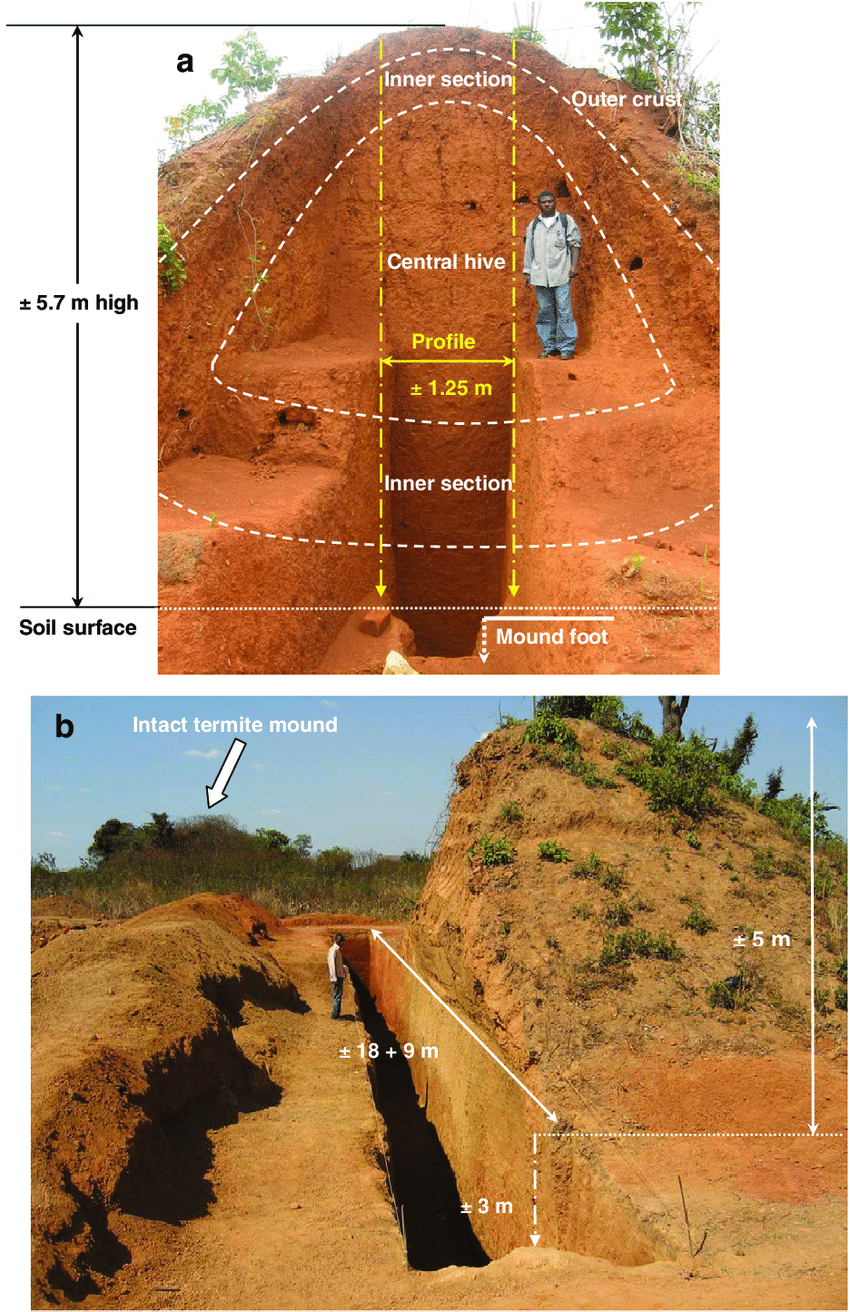

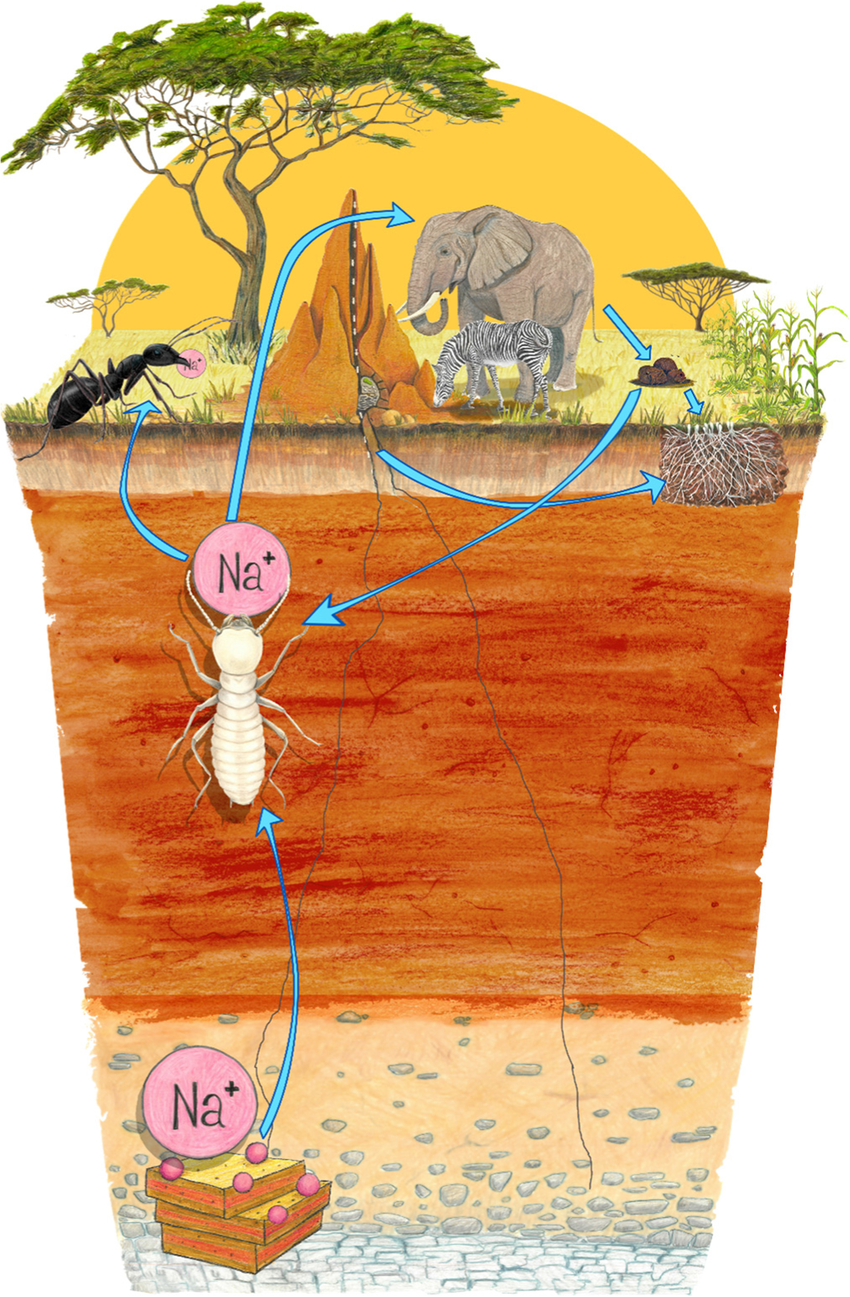

The team used advanced microscopy and chemical tracing to map the fingerprints of insect activity across Ferralsol profiles from three continents. Their findings are striking: termites, possibly in search of scarce minerals like sodium, mine materials from depths of up to 10 meters. They transport these nutrients to the surface, where ants help redistribute and stabilize them—creating honeycomb-like soil microstructures that resist compaction, retain water, and allow roots to thrive.

Yet this partnership is under threat. In regions where native vegetation is converted to cropland, termite and ant populations decline rapidly. In Ivory Coast, the team observed a 60% drop in these soil-structuring insects just five years after agricultural expansion. Water retention and crop yields followed the same downward trajectory.

For scientists, the implications go beyond soil science. The biological design principles embedded in Ferralsols could inspire new directions in vernacular architecture, permaculture, and even regenerative land use. Termite mounds—known for their natural ventilation and climate regulation—have long fascinated architects. Now, this new research offers a soil-level perspective on bioengineering that’s been quietly evolving for tens of thousands of years.

Related: Dubai develops a museum for soil

“We must develop farming systems that work with these natural builders, not against them,” said Bruand. “The future of tropical agriculture may depend on whether we can protect these underground allies.”

Designers and architects interested in sustainable land-based development can take cues from this research:

- Leave vegetation corridors between cultivated fields to allow for recolonization of native insects.

- Explore soil biomimicry by replicating termite-built structures in agricultural substrates.

- Develop bio-inspired building materials that mimic the thermal and structural logic of insect habitats.

Policymakers, too, may begin using insect abundance as a new indicator of soil health. Researchers are already exploring rapid field tests to measure the “biological soil structure potential”—a kind of ecological fingerprint left by these ancient builders.

The message is clear: these insects have solved problems of drainage, drought, and compaction long before humans ever arrived. Protecting them isn’t just conservation—it’s smart design.