Running 26.2 miles at speeds most people cannot hold for a single mile requires years of targeted preparation. The men and women finishing major marathons in times under 2 hours and 10 minutes follow training systems built on exercise physiology research, altitude manipulation, and precise intensity control. Their weekly routines look nothing like recreational running programs, and the reasoning behind each session comes from decades of scientific study into human endurance limits.

The Numbers That Separate Elite Runners

A laboratory measurement called VO2 max tells researchers how much oxygen an athlete can use during intense exercise. Average adults test between 30 and 45 ml/kg/min. Elite endurance athletes score between 65 and 80 ml/kg/min. This gap explains why a professional marathoner can hold a pace that would leave an untrained person gasping within minutes.

Another marker called lactate threshold determines how fast someone can run before acid accumulates in working muscles. In untrained people, this point arrives at roughly 76.6% of their VO2 max. Elite runners push that boundary to about 82%. The practical result shows up on the track: professional marathon runners maintain lactate threshold speeds of 18 to 21 km/h, and they can hold that output for hours.

These numbers do not arrive by accident. Targeted training over many years shifts both measurements upward.

Fueling During Long Runs

Marathon training sessions that extend beyond 90 minutes require athletes to consume carbohydrates mid-run. The body stores roughly 2,000 calories of glycogen in muscles and liver, and prolonged efforts deplete these reserves at a steady rate. Runners practicing race-day nutrition strategies learn to time their intake and test products like sports drinks, bananas, and energy gels to find what their stomachs tolerate at pace.

Elite programs treat fueling as a trainable skill. Athletes experiment with different carbohydrate sources during weekly long runs, aiming to consume 60 to 90 grams per hour during competition without gastrointestinal distress.

The 80/20 Rule in Weekly Training

Dr. Stephen Seiler studied training logs from world-class endurance athletes across multiple sports. His research found a consistent pattern: these athletes spent approximately 80% of their training time at low intensity and 20% at high intensity. They did not arrive at this ratio through instruction. They gravitated toward it naturally over years of competition and trial.

The logic makes sense when you consider recovery. Hard sessions break down muscle fibers and stress the cardiovascular system. Easy sessions allow repair while still accumulating mileage. Professional marathoners log between 110 and 140 miles per week during peak training blocks. John Korir, winner of both Chicago and Boston marathons, has reported peak weeks exceeding 160 miles.

Running that volume with too many hard days leads to injury and burnout. The 80/20 split lets athletes absorb the workload.

Why East African Runners Dominate

Of the 100 fastest marathon times ever recorded, 89 belong to Kenyan or Ethiopian runners. Part of this comes from cultural factors: running represents a pathway to financial success, and communities identify talented youth early. Part of it comes from geography.

Kenya’s Iten and Kaptagat training areas sit at 2,500 meters above sea level. Ethiopian elites train at elevations between 2,355 and 2,890 meters in places like Addis Ababa and Entoto. At these altitudes, the body produces more red blood cells to compensate for thinner air. When these athletes descend to race at lower elevations, they carry that extra oxygen-carrying capacity with them.

Western runners often travel to these locations for training camps or use altitude tents to simulate the effect at home. The adaptation takes weeks to develop and fades within a similar timeframe after returning to sea level.

Periodization and Training Phases

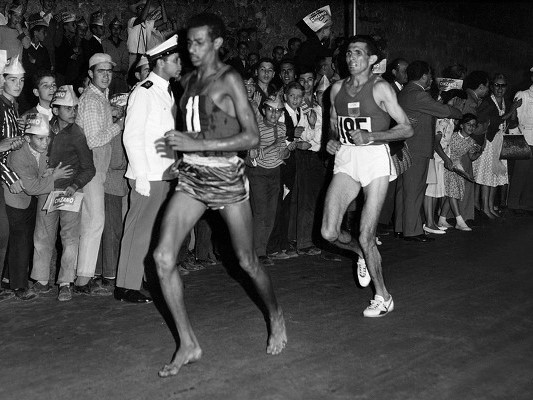

Abebe Bikila – Wikipedia 1960 Rome Olympics

Elite programs divide the year into blocks with distinct goals. A base phase focuses on building aerobic capacity through high mileage at comfortable paces. A sharpening phase introduces faster workouts that simulate race conditions. A taper phase reduces volume before competition so the body can absorb previous training and arrive at the start line fresh.

Each block might last 4 to 8 weeks depending on the athlete’s race schedule. Coaches adjust based on how the runner responds, using blood tests, heart rate data, and subjective feedback to modify plans.

Recovery as Training

What happens between runs matters as much as the runs themselves. Sleep research shows that endurance athletes need 8 to 10 hours nightly to support muscle repair and hormonal balance. Many professionals nap during the day, particularly after morning sessions.

Massage, ice baths, compression garments, and stretching routines fill the hours when athletes are not running. Some of these methods have strong research support; others work primarily through placebo or relaxation effects. Either way, the time spent on recovery allows for the high training loads that produce results.

The Mental Component

Running at lactate threshold pace for over 2 hours requires mental discipline that cannot be measured in a laboratory. Elite marathoners develop this through years of hard training and racing. They learn to tolerate discomfort, to break races into smaller segments, and to maintain focus when fatigue accumulates.

Coaches incorporate specific mental training techniques, including visualization of race scenarios and practice at running even splits when the body wants to slow down. These skills take repetition, and they separate runners with similar physical abilities.