Heinz J. Sturm is a system architect and analyst exploring integrated climate, energy, water, and health systems as initiator of the Bonn Climate Project and developer of Ars Medica Nova.

Across Western countries and large parts of the Middle East, health systems are approaching a structural turning point.

Rising costs, chronic disease, demographic change, and environmental stress are exposing the limits of existing healthcare models.

What is becoming visible is not a crisis of medicine, but a crisis of system design.

Policymakers are increasingly recognizing that the future of health prevention and healthcare cannot be secured through medical expansion alone. Long-term stability will depend on how foundational systems—water, food, energy, and living environments—are designed and integrated.

In this article, I point out why health must be understood as the outcome of coherent system architectures. The question is no longer whether health systems will need to change, but whether they will be redesigned deliberately—or forced to change under pressure.

From System Loss to System Design – Why Health Begins Long Before Hospitals

In many countries, healthcare costs are rising faster than economic growth. At the same time, chronic disease is placing lasting pressure on public budgets. This situation is often described as a medical crisis. In reality, it is a structural one.

Health is not a medical sector.

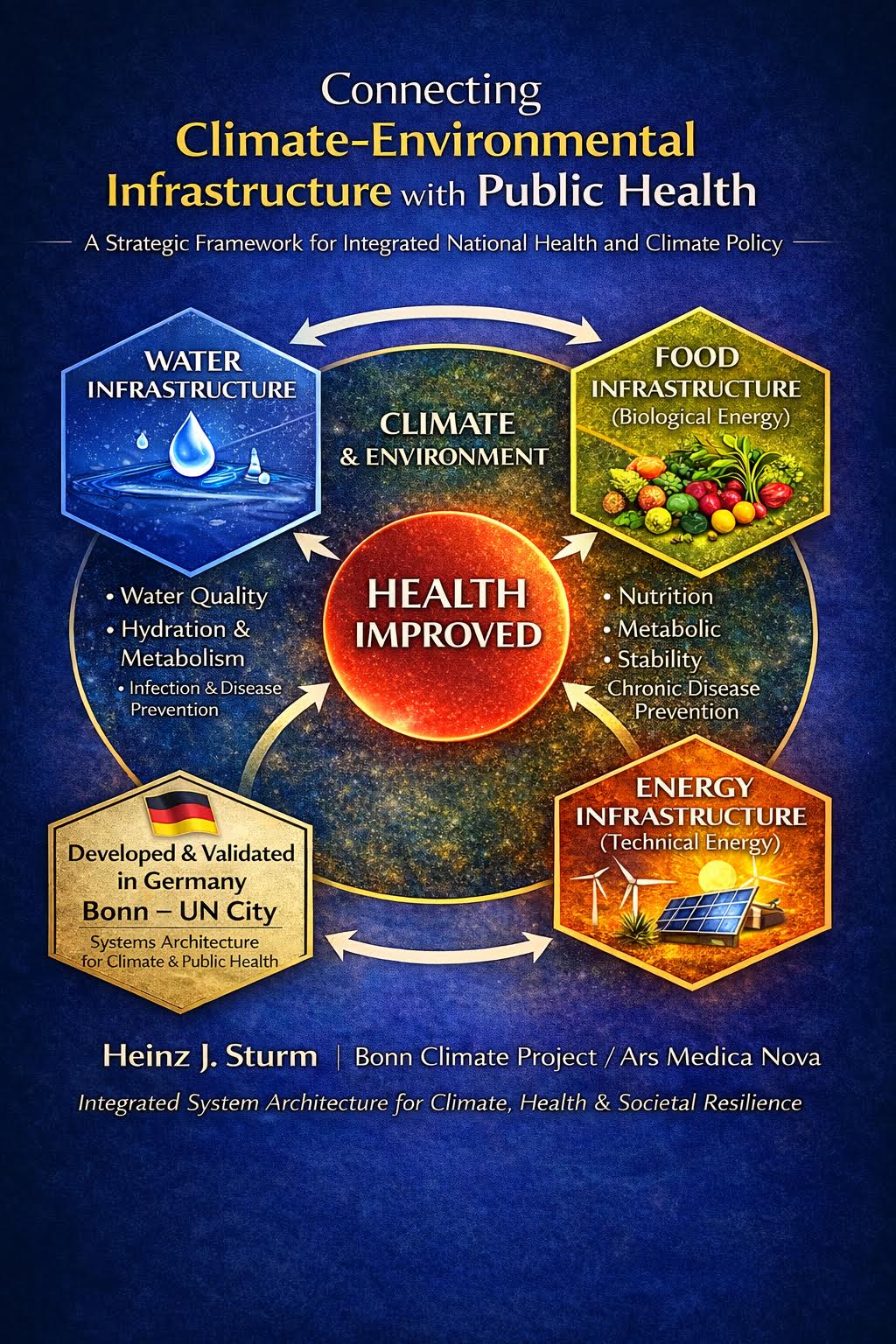

The model shown describes health not as an isolated medical service, but as the outcome of a continuous energy and material system linking water, food, living systems, and human physiology.

At the foundation lies water—not only as a resource, but as a primary form of biological energy. Clean water carries minerals and energy into soils and plants. Through food systems, this energy is transferred to animals and ultimately to humans.

Nutrition, in this context, is not merely the intake of substances, but the transfer of biologically active energy required for cellular function, metabolism, immune regulation, and physiological balance. Health emerges from the availability and quality of this energy flow.

Cells can only function stably when continuously supplied with clean, low-resistance biological energy derived from water, minerals, and food. When this energy and material flow is disrupted—through poor water quality, degraded soils, or nutrient-poor food—physiological stress and disease risk increase.

Technical energy systems complement this biological cycle. They enable water treatment, irrigation, agricultural production, storage, and food distribution. When properly designed, they support biological energy flows rather than displacing them.

The interaction of biological and technical energy and material systems strengthens resilience, reduces long-term health costs, and stabilizes societies. Health appears in this model as the result of functioning systems—not as the product of isolated interventions.

It is the outcome of systems.

Modern health policy focuses primarily on hospitals, pharmaceuticals, and clinical care. These are necessary, but they intervene late—after imbalances have already emerged.

Health begins earlier: with water quality, food systems, living environments, and the ecological conditions of daily life. When these systems are unstable or poorly regulated, disease rates rise and healthcare systems enter a permanent repair mode.

This is not a failure of medicine.

It is a failure of system design.

Historically, this understanding of health was self-evident. Medical traditions across the Levant and the wider region viewed health as balance between human beings and their environment. Water, food, climate, and lifestyle were central medical factors. These systems were preventive and sustainable over time.

Today, it is becoming clear that intervention-based health systems—however effective in acute care—face economic limits. Even the countries that developed them struggle with rising costs and structural overload.

A different path is possible.

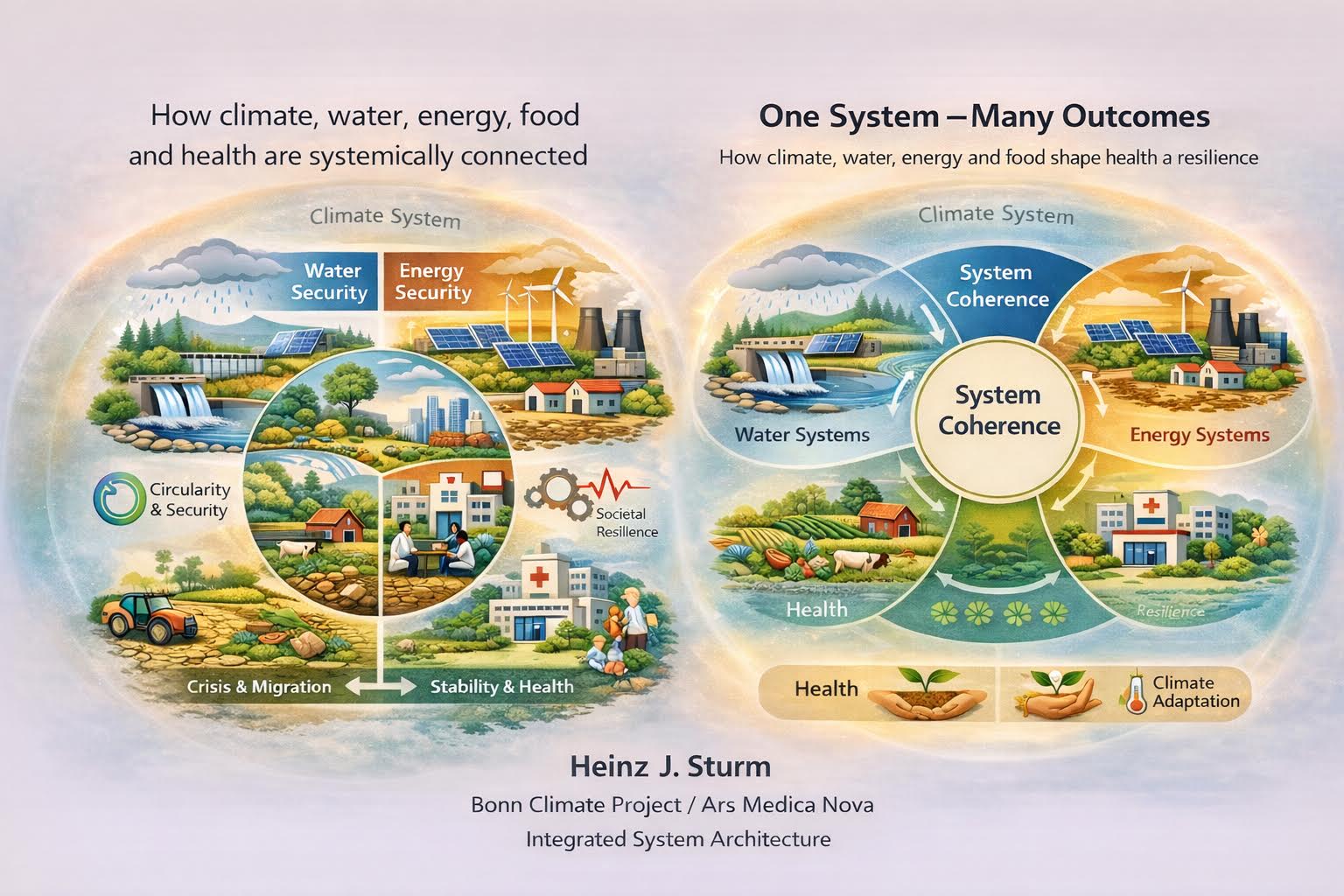

Where water systems are stable, nutrition improves. Where nutrition is stable, human physiology stabilizes. Where living environments support biological needs, long-term health costs decline. Health does not emerge as a service delivered, but as the result of good design.

This also changes how medicine itself is understood. Originally, the physician was a system thinker. In this sense, many professions shape health—from water and agricultural experts to urban planners and infrastructure operators.

This systemic relationship is illustrated in the accompanying graphic.

What Comes Next?

If health is a system outcome, reform cannot begin with isolated projects. It must take place at the level where systems are designed: states and ministries.

The next step lies in developing national health architectures that integrate water, food, living environments, and infrastructure as a coherent foundation. The goal is no longer intervention, but prevention—and long-term stability.

___

Heinz J. Sturm is a system architect and analyst working at the intersection of energy, water, health, and societal resilience. He is the initiator of the Bonn Climate Project, where he develops integrated system frameworks linking climate action with public health and long-term stability. Sturm is also the developer of Ars Medica Nova, a conceptual platform exploring new models of preventive health that draw on systems thinking, biology, and infrastructure design. His work focuses on translating complex system architectures into practical narratives for policymakers, researchers, and civil society.

i enjoy reading your articles, it is simply amazing, you are doing great work, do you post often? i will be checking you out again for your next post. you can check out webdesignagenturnürnberg.de the best webdesign agency in nuremberg Germany