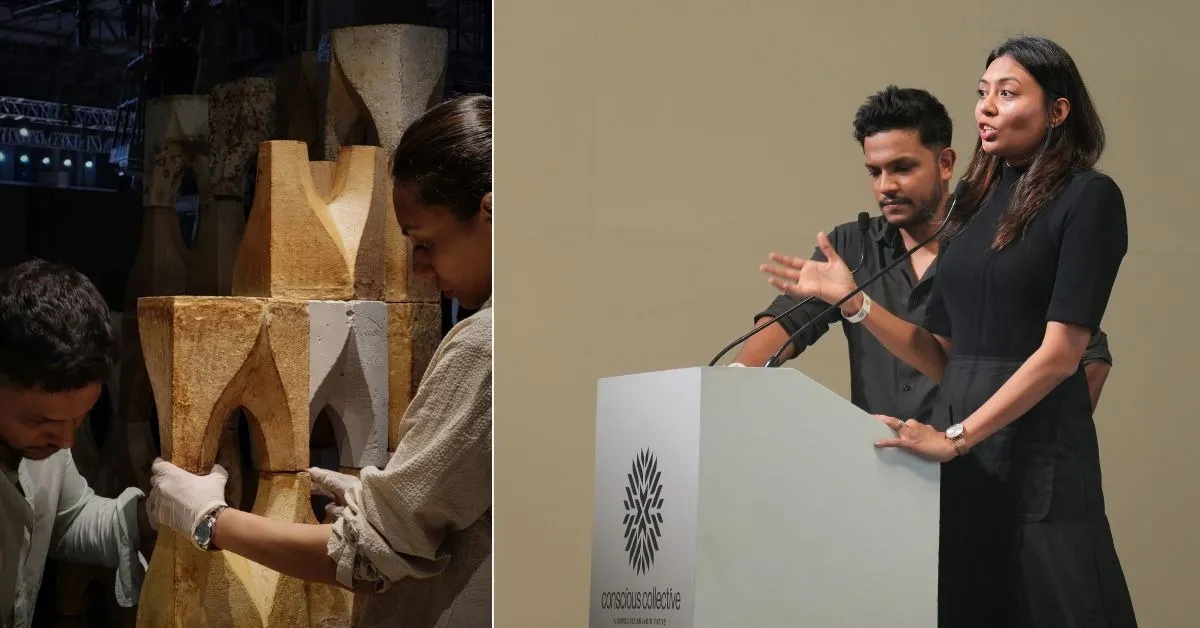

In Mumbai, architects Bhakti Loonawat and Suyash Sawant are proving that furniture doesn’t always have to be cut, nailed, or welded together. Through their design practice Anomalia, the duo is coaxing mushrooms into consoles, blocks, and textiles—lightweight, durable, and fully biodegradable pieces that challenge the way we think about materials.

Step inside a sunlit Mumbai apartment and you’ll find a console table that appears sleek and conventional at first glance. Look closer, though, and its supporting columns are not wood, stone, or steel, but mycelium—the filamentous root network of fungi.

Related: a guide to making mushroom paper

Interior architect Huzefa Rangwala, co-founder of the studio MuseLAB, was among the first to experiment with these pieces. “We bought two consoles for a client project,” he explains. “They’re light, easy to move, and strong enough to hold everyday use, but they don’t dominate the space. The combination of mushroom bases with a wooden top feels familiar yet innovative.”

For Rangwala, whose work frequently intersects with sustainability, the appeal lies in supporting material innovation. “Design has to move beyond surface aesthetics,” he adds. “If new materials reduce waste and emissions, we all benefit.”

Globally, mycelium has been explored as an alternative for packaging, textiles, and even fashion. In India, however, furniture applications remain rare. Anomalia’s “Grown Not Built” collection changes that by offering modular blocks made from agricultural waste bound with mycelium.

Each block weighs only 1.5 kilograms, yet can withstand compressive loads of up to 1.5 tons—a tenth the weight of concrete with comparable strength. From these building blocks, Bhakti and Suyash assemble stools, tables, shelves, or partitions. A second line, “MycoLiving”, extends their experiments into textiles, producing pliable sheets of mushroom material as vegan alternatives to leather for seating and upholstery.

“The beauty of mycelium is its circularity,” Bhakti says. “Conventional furniture ends up in landfills. Ours can return safely to the soil within six months.”

The couple first tested mycelium during the pandemic, growing fungi in cupcake trays in their apartment kitchen. Realising its structural potential, they scaled up experiments into bricks, partitions, and eventually furniture. By 2022, they had launched Anomalia.

Just three years later, their mushroom furniture was showcased at the Venice Biennale in 2025, and in Seoul they unveiled a 4-meter-wide mycelium façade—evidence that fungi could go beyond interiors into architecture itself.

Sustainability Rooted in Waste

India’s agricultural sector generates vast crop residues, much of which is burned, worsening air pollution. Anomalia diverts this waste stream, binding it with fungi to create new material value.

“It’s biodegradable, strong, and avoids landfill,” says Suyash. “We don’t want our work to look like ‘eco furniture.’ It should feel elegant and timeless while also being regenerative.”

Designing with fungi isn’t like working with cement or timber. Mycelium growth is vulnerable to contamination and moisture, requiring controlled airflow and drying. Untreated, it doesn’t hold up well outdoors. To extend its life, Anomalia uses natural coatings like beeswax or lime plaster and bakes blocks to deactivate growth while preserving strength.

Financially, too, the process is demanding. The pair initially relied on savings and small grants, while running their architectural practice in parallel. “It’s bootstrapped but intentional,” Bhakti notes. “We want to grow responsibly, not mass-produce.”

So far, Anomalia has sold around 100 mycelium blocks and a handful of furniture units in Mumbai and Surat, with plans to set up manufacturing in India while collaborating with larger suppliers abroad. But the ambition stretches further.

“We dream of growing an entire house—walls, partitions, even the roof—out of fungi,” Suyash says. “That would demonstrate its true structural potential.”

For Anomalia, mushroom furniture is not just about creating new products; it’s about re-imagining design as a circular system. Materials, they believe, should serve their purpose and then return gracefully to the earth.