Outside of developed Western countries, many people’s health and survival depends on access wildcrafted plant medicines. In Africa, where infectious diseases and parasites are still a major threat, up to 80% of the population is are more likely to get their medicine from a tree or farmer’s market than from a sealed blister-pack at pharmacy. Natural plant medicines are not unsubstantiated folklore; they are being increasingly proven by scientists, extracted and mass marketed by pharmaceutical companies.

This is because nature produces fantastically complex molecules that no medicinal chemist could ever dream of. Botanical drugs tend to be naturally in sync with our bodies because humans evolved from plants, and we share much of the same basic DNA. Out of 177 drugs that have been approved worldwide for cancer, more than 70% are based on natural plant compounds or mimetics – synthetics that were directly inspired by plant compounds.

There is a huge problem with deforestation in many developing countries, and sadly, some of the places that have the richest botanical diversity are hit the hardest. In countries where many people don’t have access to modern amenities like electricity and natural gas, there is a urgent daily need for firewood. An estimated 90% of the forests in Haiti have been chopped down by people who needed charcoal to cook for their families. On the Southeast Asian island of Borneo, where half of all households subsist on less than $120 USD per month, the temptation to clear forests for plant palm oil plantations, timber or paper pulp is simply too strong to resist.

Locals know that their forests are dwindling but oftentimes they just can’t stop the highly determined & organized ‘mafia’ of poachers and loggers. This has caused current plant extinction rates to skyrocket to least 100 to 1,000 times higher than the natural background extinction rate, which is the rate at which species naturally go extinct without human intervention.

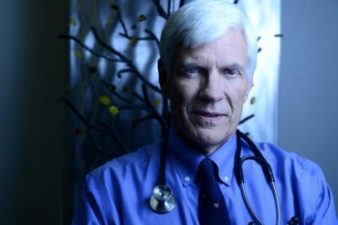

This means that 25% of the world’s conifer trees and as many as 15,000 known medicinal species are now endangered. “A vast majority of the plants in the world have not yet been explored for medicinal potential by scientists” says Dr. Bomi Joseph, a plant researcher and Director of the Peak Health Center in California. “It is especially tragic that plant species are so rapidly disappearing at the same time that research & analysis tools are finally becoming more powerful and accurate,” he says.

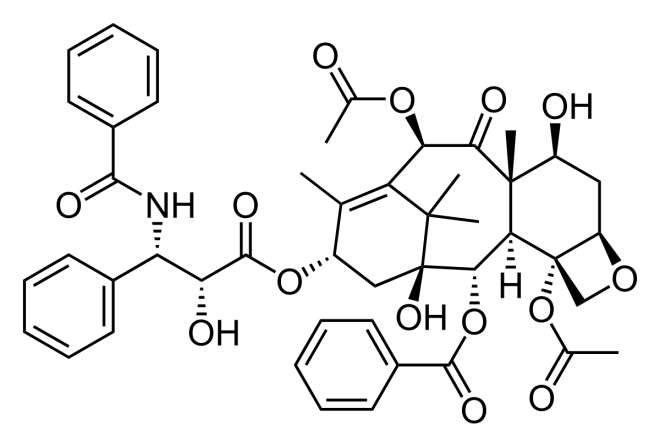

The Pacific Yew (Taxus brevifolia) tree bark is the original source of paclitaxel, a potent botanical chemotherapy agent that can is used to kill ovarian, breast and lung cancers. It was discovered in an exploratory plant screening program sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. It works by inhibiting a natural compound that allows cells in the body to divide, thus preventing the cancer from growing. It is a complex molecule that is extremely difficult to make from scratch in a chemistry lab, but the Pacific yew tree makes it effortlessly in its bark out of soil nutrients, CO2, water and sunshine.

(Image: Wikipedia, Creative commons)

From 1967 until 1993 almost all the paclitaxel produced was derived from the bark of wildcrafted Pacific yew trees. The process of harvesting the bark kills the tree and in 2011 the tree was placed on the endangered species list. Finally, but a bit late, a method to make the drug semi-synthetically out of liquid plant cultures that don’t require destruction of the tree is now used.

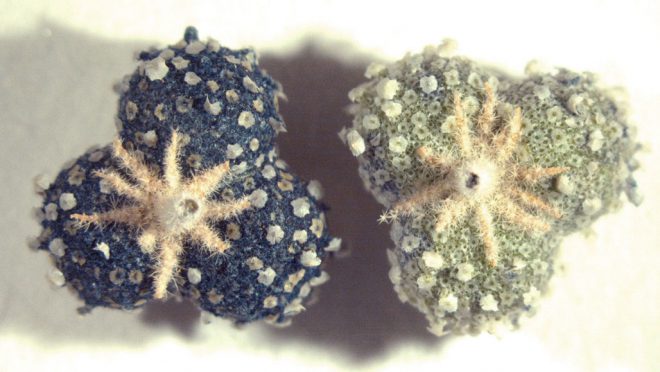

Himalayan Mayapple

The Himalayan mayapple plant (Podophyllyum hexandrum) produces podophyllotoxin, which is a key compound used to produce etoposide – a chemotherapy medication that is used against lung, testicular and ovarian cancer.

The plant has been over-harvested while at the same time its natural habitat in the Himalayas has been heavily deforested. It is currently listed as an endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

The Calophyllum Story

In December 1986, the arboretum at Harvard University got involved with a project sponsored by the National Cancer Institute to find antitumor plant compounds in Asian forests. They wrote to a state government in Borneo and got permission to collect plant specimens. Research associate Dr. John Burley and a forest officer set off into the tropical forests and swamps and collected all the flowering and locally-revered medicinal plants that hadn’t already been screened and catalogued.

Years later, one of the plant specimens from a calophyllum tree, labeled Burley #351, was analyzed and found to stop the HIV virus from replicating. In 1992 scientists returned to the area where the sample had originally been collected, accompanied by local botanists, and the tree was nowhere to be found – presumably cut down. They tried to locate trees of the same species in the nearby areas but the closest ones they found did not contain the same active compounds as Burley’s original sample.

After a long and difficult search a calophyllum tree with the same active compound, which became named calanolide A, was eventually located at a botanical garden in Singapore. The Borneo state government formed a pharmaceutical company to develop calanolide A into a drug and in 2016 they announced successful completion of Phase I clinical trials on humans. A structural analog named F18 was created in 2017 that is believed to have even more potent anti-HIV activity than the original molecule.

Only half of Borneo’s forests remain standing today, and those that still remain are disappearing at a breathtakingly brisk rate of 130,000,000 acres per year. The plants described above are just a handful of examples out of thousands of species with equal or greater potential.

“There is no telling how many botanical drug breakthroughs or desperately-needed cures go up smoke or down with the stroke of a chainsaw every year,” says Dr. Bomi Joseph. “Seeing that we can’t control & protect every forest on earth – we need to make plant specimen collection and analysis a top priority while we still have the chance to.”