“It was the best butter, you know,” said the March Hare.

The current butter crisis in Israel evokes the Mad Hatter’s tea party in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. The same surreal logic reigns here.

Once there were two dairies producing butter in Israel, Tara and Tnuva. Tara, citing profit loss for reasons explained below, stopped producing butter. And the Tnuva brand butter has been as scarce as hen’s teeth for over a year now. Shoppers drive from market to market in hopes of finding, and pouncing on, the familiar silver package with its logo of a little red cow shed. When a butter cache appears in a local store, people light signal fires to one another via the social media: “I found it here – hurry up and get some before it’s gone!”

Almost everyone is hoarding a cache of butter in their freezer. And the feeling is almost of buying on black market, with a lucky score something to brag about.

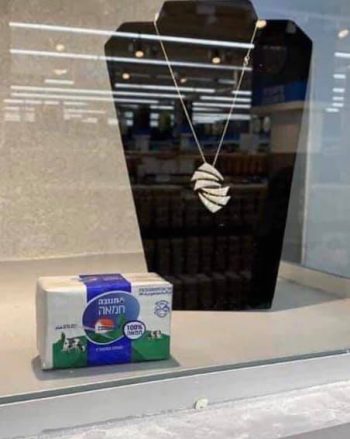

People are taking the butter drought in fairly good humor now, but the grumbles are gathering weight and starting to sound louder, as shown by this photo showing a package of increasingly rare Tnuva butter posed next to a silver necklace.

The public has been offered a variety of imported butters – from Holland, Belgium, Lithuania, France, and other countries. A strange product made of mixed butter and oil sits on the shelves, rightly viewed with disdain. These imported butters are far more expensive than the dear departed Israeli stuff. But where has the native butter gone?

Tnuva, Israel’s largest food company, began close to 80 years ago as a cooperative owned dairy farmers from kibbutzim and moshavim. By 2007, the British firm Apax owned 56.05% of Tnuva. The Israeli investment company Mivtach Shamir held, and still holds, 20.67% of Tnuva, and a minority of 23.3% is owned by kibbutz partners who refused to sell their shares. In 2014, Apax sold its shares to Bright Food, China’s second largest food conglomerate.

Bright Food has been acquiring more foreign food companies in the last few years. In 2018, they bought the US meat processing giant Smithfield Foods. Previously they acquired the UK cereal company Weetabix. Meat, dairy, and breakfast cereal. One gets the feeling that all this conforms to a 10-year plan.

The Chinese takeover of Tnuva wasn’t popular in Israel. Voices against the purchase were heard in the Knesset Economic Affairs Committee at the time. There was strong concern over the fact that a critically important food producer was going to be controlled by a foreign government. The Committee Chairman, MK Avishay Braverman asked the government to prevent the sale of Tnuva, to no avail.

Former Mossad director Efraim Halevy warned that the sale could jeopardize Israeli food security, and possibly go further.

“The fact that Israel’s largest food company is owned by the Chinese government will lead to a situation where the company implements policies that serve the interests of China [and not Israel],” he said in an interview with Ynet. “For China, Tnuva isn’t just a food company,” Halevi added. “China is doing everything it can to involve itself in Israeli research and development. The Chinese are very creative and flexible. If we do not wake up in time we will find that they will take over not only our food, but our academia. We must organize in order to defend Israeli assets, which are part of our national security conception.”

Dairy farmers protested in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, worried that the Bright Food takeover would jeopardize previous supply contracts with Apax. The public expressed disgust but had no say in the matter.

“Regulated butter is sold in Israel for a maximum price of NIS 3.94 (approximately $1.1) per 100 grams. Many estimated that the 2018 shortage was the result of an intentional move by Tnuva, brought about by the finance ministry’s refusal to raise the regulated price of butter. Actuality, however, the company increased its production that year by nearly 20%, from 3,569 tonnes of butter produced in 2017 to 4,273 tonnes in 2018, according to a report published by Israel’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development in May.”

…”In the first half of 2019, both Tnuva and Tara cut back on butter production as it became less profitable, producing just 1,869 tonnes and 28 tonnes respectively, according to data from Israel-based sales data research company StoreNext Ltd.”

From Calcalist, some of whose sources insist on remaining anonymous:

“A Tnuva spokesperson said that the only cause for the butter shortage is a shortage in milk-derived fat, due to the limited milk production quota set by the government. Tnuva’s stock of milk fat, which it uses for butter and cream production, began running out in December last year, which could explain its decision to cut butter production in early 2019. In order to meet the demand for butter, Israel must increase milk quotas, several people familiar with the matter who spoke on condition of anonymity told Calcalist. The industry requested 60 million liters of milk a year be added to its quota to allow it to extract more fat to use for butter production, the people said.”

Israeli consumers turned to expensive imported butters. But there’s less of even imported butter now. Until recently, imported butter bore a heavy tax (from 126-140% for table butter and 144-160% for industrial butter), which importers were reluctant to pay because the government forbade selling it for more than the regulation price of NIS 3.94 per 100 grams. Many importers simply declined to bring butter in.

Attempting to save the situation, the Agriculture and Economy ministries recently decided to open a tender for importing up to 5,000 tonnes of customs-free butter, with no market price restrictions attached. But this was done too late to avert the crisis. In spite of Israeli’s reluctant acceptance of high-priced imported butter, less and less of it appears on the shelves.

In point of fact, there are currently hundreds of containers of imported foods, and butter among them, sitting in Haifa and Ashdod ports. Due to the High Holidays that occurred in September and October, the containers have not been inspected by the Ministry of Health, and so have not been released.

For the consumer, all this wrangling ultimately means less butter, and when it’s available, it’s expensive. People are currently complaining that there’s no butter at all on market shelves. This at a time when demand has only gone up, due to nutritional trends encouraging consumers to eat less GMO-based oils and trans fats.

The Economy and Industry ministries recommend getting rid of tariffs on imported butter and opening the Israeli market to competition. But under Israel’s current interim government, policy changes are unlikely to be made any time soon. In the meantime, the Agriculture and Economy ministries cite unequal distribution of import quotas and blame each other for it.

The mystery is, given the proved demand for more butter, why not allow Israeli farmers to increase milk production, thus allowing Tnuva to obtain the milk fat needed to make it? And where does Bright Food fit into this puzzle, if indeed it does?