New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is hosting an exhibition on refugee shelters to kickstart dialogue on the design challenges caused by humanitarian crises. Entitled “Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter”, the show looks at emergency housing in contemporary crisis zones. It is the first time a major museum has explored the plight of the world’s homeless.

Humanitarian design is a broad category of industrial design, architecture, and engineering that focuses on improving the human experience. In the Middle East, the term was hijacked to describe structures and artefacts designed to help refugees and displaced people cope with homelessness and lack of essential services. Think it’s a boutique niche in modern design? Think again.

One out of every 113 humans alive today is either a refugee or displaced internally in their home nation, so says the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. More than 4.8 million people have fled Syria since the onset of its civil war, and the stampede towards the borders hasn’t stopped. That’s comparable to Afghanistan, which has generated millions of refugees for decades. Turn to Somalia, Sudan, Eritrea, Iraq, Yemen, and understand the United Nations calculation that 65.8 million people are presently, and forcibly, removed from their homes.

One out of every 113 humans alive today is either a refugee or displaced internally in their home nation, so says the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. More than 4.8 million people have fled Syria since the onset of its civil war, and the stampede towards the borders hasn’t stopped. That’s comparable to Afghanistan, which has generated millions of refugees for decades. Turn to Somalia, Sudan, Eritrea, Iraq, Yemen, and understand the United Nations calculation that 65.8 million people are presently, and forcibly, removed from their homes.

These people need shelter, a specific kind of shelter that can be rapidly deployed and easily assembled with basic tools and labor skills.The MoMA exhibition assesses some iconic contemporary designs to find what works, and what doesn’t.

“This exhibition raises questions rather than tries to provide answers,” curator Sean Anderson told Fast Company. “How does architecture and design today reflect, or not reflect, these conditions of transit? In the carving up of new territories and the creation of new border systems, we begin to see how architecture plays into the spatial or geospatial ideas of identity.”

Green Prophet has written extensively on design solutions proffered to date, including 10 intriguing solutions in this 2014 post (link here). And continuing development of open-source design platforms – such as Open Architecture (formerly Architecture for Humanity) and the Open Building Institute – serve up practical, smart architecture designed by professionals and released freely for use and/or adaptation by the public with a goal of improving worldwide housing.

Designs that address the challenges of conflict and mass migration also have currency in disaster relief. Consider the looming impact of climate change on coastal communities, towns vulnerable to either severe drought or flooding, and urban areas devastated by extreme weather events. “I think with climate change we are going to see a vast influx and repositioning of what it means to be a refugee in the future,” said Anderson. So add climate refugees to the global parade.

The exhibition includes shelters from refugee camps in Kenya, Jordan, and Turkey, as well as experimental solutions by architects such as Shigeru Ban’s 1999 paper-tube structures for Rwandan refugees and bamboo houses by Norwegian firm TYIN Tegnestue.

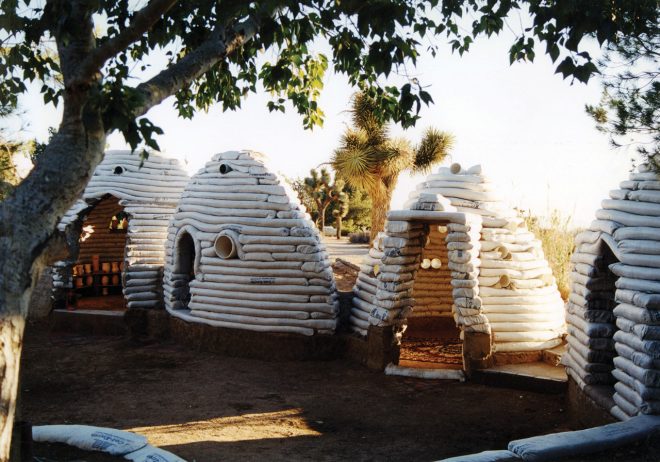

Iranian architect Nader Khalili’s sandbag shelters, seen above, are simple dirt-filled sandbags which can be hand-assembled by six unskilled laborers in a single day. “You could argue that these structures are fundamentally about materiality and the ability to move them into sites relatively quickly,” Anderson says.

Iranian architect Nader Khalili’s sandbag shelters, seen above, are simple dirt-filled sandbags which can be hand-assembled by six unskilled laborers in a single day. “You could argue that these structures are fundamentally about materiality and the ability to move them into sites relatively quickly,” Anderson says.

Those characteristics are embedded in the IKEA shelter, seen below, which can fit into two flat pack boxes that include all components plus hardware and simple tools. Fifty units can be loaded on a flatbed truck and quickly delivered anywhere that has road access.

Anderson travelled to refugee camps in Jordan, Italy and Sri Lanka to see shelters in situ, noting an absolute absence of site sensitivity. As example, Jordan’s Zaatari Syrian refugee camp is on an open desert plateau, pummeled by sandstorms and naturally teeming with scorpions and vermin.

“What was really just eye-opening to me was the lack of imagination but also consideration of where these shelters are,” he said. “It was 120°F out and you see acres and acres of metal buildings with one or two small windows. So people can’t live in these structures during the day.” Occupants have to choose between leaving doors open for added airflow, which compromised security.

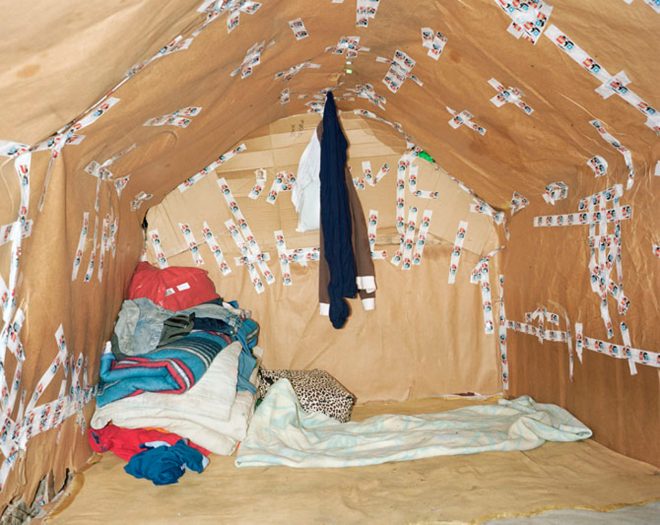

The metal cabins replaced the original UNHCR fabric tents, but residents were allowed to kep those tents – to re-purpose or sell to other refugees within the camp. “What was more intriguing to me was how [the refugees] began to manipulate and change and augment these spaces,” Anderson told Fast Company. “The most poignant moment for me was sitting for a few hours in a large tent and the man said, ‘I’m a Bedouin, I know how to build tents and I refuse to live in these metal boxes.'”

“In this desire for maximum visibility, maximum rationality, and organization, there is a lack then of individuality,” Anderson says. “These individuals who are moving or are being forcibly moved from various countries literally lose their identity to go into places that are for their own safety and security and become a number in a system that they don’t necessarily recognize or understand. Shelter is not an end in itself; it actually requires a close observation of the client. What are the everyday needs of these individuals? I would suggest that it’s more than just access to food and water, but they deserve a bit of privacy and a bit of humanity.” He added that paying attention to regional building styles from the displaced population’s homeland would make for stronger designs.

The show distinguishes short-term emergency shelters from long-term refugee housing. A refugee might live in an “interim” camp for many years awaiting a return home or resettlement abroad. Consider the Kenyan camp Dadabb which opened a quarter century ago. Many of the Syrians in Zaatari are now into their fifth year of residency.

“If we see camps as permanent impermanent conditions architecturally, what’s overlooked is the landscape and the very nature of how do we transform the landscape to accommodate these cities,” Anderson said. “Everyone I interviewed [at Zaatari] said they would rather have better telephone reception than better housing.”

Got some time (and tolerance of architectural hyperbole)? Tuck into the video above, and learn more as MoMA director Glenn Lowry discusses the opening of this exhibition and a second show entitled “How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior,” with curators Sean Anderson and Juliet Kinchin.

“Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter” will be on view starting until January 22, 2017. “How Should We Live? Propositions for the Modern Interior” will be on view through April 23, 2017.

All images from MoMA website

One thought on “Refugee architecture earns an exhibit in a NYC museum”

Comments are closed.