We speak to Shahrzad Mohtadi about the devastated drought that crippled Syria’s food centre and shook Assad’s political stability

We speak to Shahrzad Mohtadi about the devastated drought that crippled Syria’s food centre and shook Assad’s political stability

The link between climate change and political instability may still be ambiguous, but recent research is uncovering a connection between sustainable water and food policies and the survival of governments. Shahrzad Mohtadi found that whilst a prelonged drought in Syria may not have caused the political uprising, the Assad regime’s failure to deal with it effectively certainly did. “Assad promoted water intensive crops such as cotton, while not providing efficient methods of watering such crops. There were many such policies that created a scenario where the drought’s effects were even more devastating than they otherwise would have been,” say Mohtadi.

“So one can’t say climate change will create a domino effect of instability and migration whatsoever – but Syria’s case is a warning that developing nations… should create sustainable agricultural policies.” I spoke with Shahrzad Mohtadi to find out more about the devastating drought in Syria and what other Middle Eastern nations need to do to protect their dwindling water resources – and their political stability.

You have studied quite a range of subjects ranging from micro-finance in post-Soviet Tajikistan to the political transition in Myanmar. What is it that attracted you to study climate change in the Middle East?

The Middle East is a region that grips many for its political drama. As the region already suffers from a chronic water shortage and political divisions remain fierce, climate change is yet another factor that could provoke instability. Climate model uniformly predict that the eastern Mediterranean (in political terms – the Middle East) will very likely have less rain in the future. If nations in the Middle East don’t begin implementing sustainable policies for farming and water intake that take into account future drying, the problems in the region will grow even larger.

Can you tell us about your current research on the effects of climate change on human migration in the Middle East?

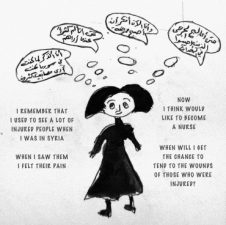

A few weeks before the March 2011 uprisings in Syria began, I applied for a fellowship regarding climate change and security. I began reading about a drought that occurred in Syria from 2005-2010, and came to understand that such a drought – in how long it lasted and how much of the country was impacted – had devastated many of the country’s farmers. Over 1.5 million farming families migrated from the rural areas of the country to urban outskirts. Once the protests in Dara’a began, and the revolution snowballed from there, I was able to show how the unusual nature of the drought, which led to a mass exodus to large cities, was an important contributing factor to the Syrian uprising.

Migration and climate change can be quite a sensitive topic to explore due to security implications and also ethical implications. Do you think the widespread concerns about climate change causing mass migration from south to the north and also political and economic instability are fair?

I don’t believe any such general statements can be made. Syria’s example of migration is unique because the Assad regime’s policies were going against any rational. For example, Assad promoted water intensive crops such as cotton, while not providing efficient methods of watering such crops. There were many such policies that created a scenario where the drought’s effects were even more devastating than they otherwise would have been. So one can’t say climate change will create a domino effect of instability and migration whatsoever – but Syria’s case is a warning that developing nations who have little control over carbon emissions should create sustainable agricultural policies.

Looking at your research into Syria, it seems that the impact of climate change-induced migration is local and regional rather than global? Is that an accurate statement?

One cannot say this migration was climate-change induced, as no single extreme climate event can ever be categorized as climate change. What we know is that such unusually long and persistent drought will be more likely in the future, which can cause migrations if governments remain ignorant to sustainable water and agricultural policies.

What have been the most surprising things to emerge from your research?

As I continued my research, I was shocked at the extent to which this drought affected rural communities in Syria. In the northeast of the country, known as the breadbasket of Syria, school drop-out rates for the drought years were up to 80%. Many schools were closed and villages deserted. Up to 90% of the livestock in the area perished. And this was a region only a few years back known as the country’s food producing center. The lack of response by the Assad regime was also shocking. For a dictatorship that wishes to maintain stability and legitimacy, the response was inadequate and later came to light during the uprising.

: Image via FreedomHouse/flickr.

For more on Syria see:

Syrian Farmers Increasingly Vulnerable

500,000 Syrians Flee Drought-Stricken Lands

How Climate Change Contributed to the Syrian Uprising