Jordanians can pick each other out by sight and last-name analysis, as accurate as DNA testing.

Jordanians can pick each other out by sight and last-name analysis, as accurate as DNA testing.

Six million “Jordanians” are a quilt sewn from disparate ethnicities and cultures, co-existing in peace while retaining the essence of their origins. This tiny nation divides itself up into groups and sub-groups and tribes and families. Jordan hosts one of the largest (by percentage of total population) immigrant communities in the world: more than 40 percent of its residents were born in other countries. Its Arab population consists mostly of Jordanians, Iraqis and Palestinians. Regional instability brings a steady flow of Egyptians, Libyans, Lebanese and Syrians.

Non-Arabs pour in too. There are Turkmans, Chechens, Circassians and Romanis. Half a million Assyrian Christians rolled in during the Iraq War. And then there are migrant workers, Southeast Asians who saturate the local domestic and construction workforce.

But these are the easy lines of division. It’s the heightened attentiveness of “true” Jordanians to the micro-populations within their own society that I find fascinating. How to explain this uber-sensitivity to “tribe” in modern, internationally-savvy Amman? I’ll make an unscientific stab at answering my own question: the best camo tent?

I think it comes from the Bedouin.

Let’s say that “true” Jordanians are the people actually born here. With parents and grandparents and great-grandparents who were also Jordan-hatched. They self-categorize as Palestinian Jordanians, and Gulf Jordanians, and Bedouin Jordanians, to name three.

These distinctions are mostly lost on me. I can’t see the subtle changes in dress or food; I’m deaf to accents since I don’t speak Arabic. The only sub-sect that stands out to me is the Bedouin, and only those still embracing a semi-nomadic life.

Their tents line the hills ringing Amman; they graze their animals in the damndest places. Local friends test me to see if I can tell a gypsy compound from Bedouin: I’m “right” half the time, but I don’t think they’re too sure themselves (although most boast Bedouin heritage, I think it’s the Middle East version of America’s “I’m part Cherokee”.).

On my fifth run to Petra, I outed myself as a tourist and bought a copy of Married to a Bedouin, by Marguerite van Geldermalsen, a New Zealander who met and married a Bedouin souvenir-seller from Petra in 1978. They made their home in a 2,000-year-old cave. She converted to Islam, learned Arabic, and gave birth to three children. She was living the Bedouin dream, and I hoped her book would let me see inside her tent. I wasn’t disappointed.

Poking around to learn more about these remarkable people, I came across a short documentary film featuring Bedouin children living in Bekaa, Lebanon. As the kids share their daily routines, their play and work, their hopes and dreams, a tiny flap in the tent is lifted. It’s an amazing piece.

Passing daily by the Bedouin tent camps, making occasional roadside stops to buy tomatoes and strawberries, I never really thought about their lifestyle. It opened my eyes and motivated me to learn more.

The Bedouin defer to a hierarchy of allegiance based on kinship

Loyalty to nuclear family, or bayt, is primary, with a family typically consisting of a married couple, their children, and perhaps adult siblings or grandparents.

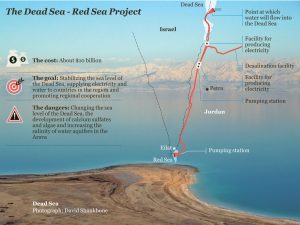

Extended family comes next (Cousin Ahmed, Uncle Ali), and this grouping spans generations. Then there’s the tribe (the Al Howaitat is one of Jordan’s largest) led by a Sheik, who mediates between tribe and outsiders. There’s power in tribe: Bedouin in Mafraq effectively blocked Jordan’s nuclear ambitions in that province; another tribe is causing headaches to the Disi Waterline project.

Groups can also be connected by their herd type. Although family is key, tribes are fluid, absorbing new members as they roam.

This framework delineates how the Bedouin settle disputes, maintain justice, and cooperate on common interests. They are fiercely independent and obey strong codes of honor, underpinned by traditional justice systems.

In the mid-nineteenth century, large numbers of Bedouin across Midwest Asia started to leave their traditional, nomadic life to settle into cities. Aspects of climate change, like severe drought, forced many to abandon herding. Rapid urbanization throughout the Middle East offers an increased standard of living that could be supported with conventional, and available, jobs.

There’s a lot of information out there about the Bedouin. Join me in learning more about them before these remarkable people are completely absorbed into the global soup.