Syria faces a severe drought. A shift in weather patterns, or just a dry season?

Syria faces a severe drought. A shift in weather patterns, or just a dry season?

A severe water shortage in Syria is forcing farmers to look for alternative means of livelihood but the drought’s impact doesn’t end with the crops.

Around a quarter of a million Syrian farmers have been forced to abandon their land over the last two years following three years of drought and failed crops. It’s one of the worst water crises in recent years with residents in Damascus and other major cities putting up with periodical water cuts during off-peak hours.

The crisis is not only the result of several years of below average rainfall but also the rising needs of a growing population, in a country with more than 20 million people and an estimated growth rate of 2.1%.

Syria’s main sources of water are the Euphrates River, the Tigris River, the Orontes River and ground water. Syria’s economy relies heavily on agricultural export, a strategy which is being called into question by experts.

“Syria has previously, and is still, subsidizing wheat production to quite an extent,” said Dr. Anders Jagerskog, project director at the Stockholm International Water Institute. “But this is getting increasingly impossible to uphold, because more people need to be fed by agricultural produce and water is needed in other sectors as well.”

Almost a fifth of the country’s GDP is made up of agricultural output and the declining yield is having a knock on effect on the rest of the economy. Syrian officials estimate that up until a few years ago, almost 90% of Syria’s water supply was being invested in agriculture.

Jagerskog said agricultural policies were being reexamined throughout the Middle East to make water conservation more effective, but were encountering obstacles.

“The agricultural lobby in Syria, as in most countries in the Middle East, is forceful, and there is a historic reason at play, in that these countries have traditionally produced most of the foodstuff they need themselves,” he told The Media Line.

“On top of that, there is a security reason. One would not like to rely too much on imported food, especially in this region. You’d like to have food secured by your own supplies.”

It should be noted that Syria is not the only drought victim in the region. Turkey and Iraq are also facing a water crisis, with Iraq blaming the reduced water flows on Turkey and Syria, which has heavily dammed some areas.

In early September, irrigation ministers from the three countries met in Ankara to discuss water shortages and the management of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which run through all three countries.

The discussions came on the backdrop of a diplomatic row between Syria and Iraq over allegations that Syria is harboring terrorists, after suicide truck bombings in Iraq last month killed more than 100 people.

Both Iraq and Syria want Turkey, the upstream country, to increase the flow through its network of dams, but the meeting was said to have ended without any significant results and without a pledge from Turkey to increase water flows.

Walid Saleh, a water expert and regional coordinator for the MENA (Middle East and North African) countries at the United Nations University, said that talks of a major water crisis may be exaggerated and this could be no more than a routine dry cycle.

“In the past few years we’ve noticed the rainy season shifting,” Saleh told The Media Line. “In previous years the rains started in early November and continued until April or May, but recently we’ve seen only a few sporadic rainfalls until December and then in February and March there will be more rainfall. For farmers this is not good news, because if you don’t have the rainfall early in the year, in November and December, then you will have a bad season because wheat and barley need the rain early on.”

In the past, Syria exported wheat to Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia, but in 2006 and 2007 Damascus was forced to import wheat.

In order to reverse this, Saleh said, measures should be adapted based on an in-depth analysis of the weather pattern.

“If the rainy system is shifting the way it has in recent years, then maybe [farmers] also have to shift the way they cultivate their land. Instead of sowing seeds in November and waiting till February without rain, the pattern could be shifted to sow the seeds in February just before the rainy season starts.”

But a change in cultivation patterns also has wider security and socio-economic implications.

“The number of people affected in 2007-8 was about one million, this represents people who depend on agriculture, and for whom this is their livelihood. But in addition, the socio-economic dimension has to be taken into consideration. If there is a shift, like importing virtual water by importing wheat, at the end of the day you’re talking about one million people who have lost dependence, this is the only income they have,” he said.

“When a country is forced to meet the demands of its people for wheat and barley, they have no choice but to import, but this is a short-term solution. You meet the demand, yes, but what will you do about employing those people? How will you compensate them? How will you train them to do something else? This takes a huge amount of effort and money and some policies and regulations have to be put in place.”

A Syrian water engineer with extensive experience in the public sector said there have been major changes in the past two years to meet the water demands in the country and change irrigation habits among farmers.

One of the changes is to introduce modern irrigation methods such as drip irrigation, which is more pinpointed and is less wasteful than flooding.

The government is already witnessing a decrease by almost 10% in water used in Syria for agriculture, and the produce yield is higher. The government is giving farmers interest-free loans and offering other financial incentives to use more modern and more economical irrigation methods.

“At present it is not compulsory but we will make it a law,” the engineer said. “We are changing the kinds of crops we grow to ones that don’t consume a lot of water. We’re lessening the amount of cotton irrigated areas and we are only applying our interests to strategic crops like wheat and sugar beet.”

As to desalination, Syria is currently experimenting with desalination on a small scale, though at present, the technology makes a cubic meter of desalinated water too expensive to be worthwhile.

But Saleh says desalination is the only viable alternative for the water industry in the future.

“The whole region is moving in that direction,” he said, “and in a few years we will see more desalination plants in Jordan and the lower parts of Syria. I don’t see any other option. I think that because water is a trans-border resource, regional cooperation is needed to solve the problem of meeting the demands for water, whether for agriculture or for drinking water.”

This article by Rachelle Kliger was republished with permission of The Media Line, the Mideast News Source.

More on drought in Syria:

Syria Suffers Severe Water Shortage

Has Climate Change Killed 160 Syrian Villages? Mass Evacuation

Syria and Jordan’s Dam Will Cut Off Israel’s Supply

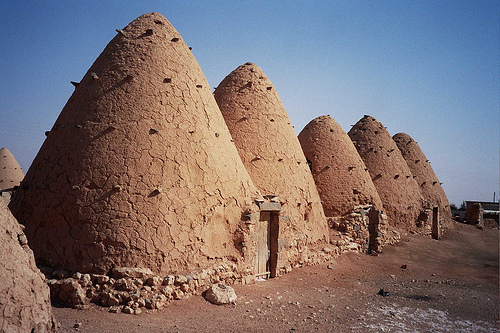

Image of Syrian beehive villages by upyernoz

7 thoughts on “Environmental Impact of a Syrian Drought”

Comments are closed.