I am really not the right person to be reviewing “Nature’s Due” by Professor Brian Goodwin from Shumacher College in the UK. It is based on some quite complicated biology, a subject that I haven’t studied formally since I was 14. James sent me the book in September, and I’ve only just finished it now, after several tactful reminders from James. As you can infer from that, it’s been a bit of a struggle.

However, I’m really glad that James stayed on my case about this, because “Nature’s Due” is a fascinating and important book. It’s one of those books that can furnish you with a couple of serviceable building blocks for a worldview.

Goodwin’s guiding question is: what would it take for our culture to interact with the world in a mode of engaged, evolutionary participation rather than in a mode of dominance and control?

He lists the familiar litany of environmental failures engendered by the dominance and control model (GM crops, degraded food supply, ugly, dysfunctional cites etc.) and asserts that the root cause of this cultural attitude is dualism: our predilection for seeing nature as inert stuff to be acted on and transformed for our benefit through the agency of human will and subjectivity.

Sometime shortly after the Renaissance, claims Goodwin, we disenchanted the world. Consciousness, intelligence and freedom were arrogated to the human realm, while the physical world was conceived as a mere machine.

So far, this is all fairly standard green cultural criticism. Cartesian Dualism has always placed in the top three of any list of the usual suspects in Western thought for creating the spiritual conditions that have allowed us to wreck our physical environment. Goodwin’s originality is to propose a reframing of our worldviews based on cutting edge research in biology that has emerged over the past 5-10 years.

The first prop of his argument is a body of work that has attempted to bring the study of qualities, including human affective and emotional responses within the domain of scientific study. For example, it turns out that there are high degrees of agreement when you ask people to ascribe emotional states to a pig. Intersubjective consensus can provide a basis for studying qualitative phenomena that cannot be measured. One small blow against the subject-object division.

A Survey In Contemporary Genetics

Much more interesting, and central to his argument, is the work that Goodwin surveys in contemporary genetics. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, most biologists thought of DNA as a sort of computer program. It was the code that instructed organisms how to grow. This belief drove the development of the epic genome mapping program that was finished in 2001.

However, as the genome project neared completion, biologists realized that it was not so much fulfilling their expectations as transforming them. It turned out that genes to do not condition the structure of living things in any deterministic way. We now know that a gene can be “read” (my quotation marks) by a cell in hundreds of different ways, each one resulting in a different protein. “For example, in the hair cells of the inner ear of a chick there is a gene that can be translated into 576 different proteins each one altering the tuning of cells to sound frequencies.”

So if genetic structure does not allow us to predict morphology as we had hoped it would, what then have we learned from the whole genome project?

Goodwin argues that a different metaphor for the genome is emerging from the work of biologists like Evelyn Fox Keller and Anton Markos. Rather than understanding DNA as a computer program, we should instead conceive it as a kind of a “text” containing a range of developmental possibilities that is “interpreted” by cells through interaction with their environments.

Cells Search for Meaning

Cells “read” their genes so as to realize the possibilities of growth that will tend towards the creation of complex, efficient, coherent and aesthetic biological forms (beauty being a characteristic of efficiency, complexity and coherence.) He ascribes the term “meaning” to the object of organisms’ search for such elegant solutions to the problems of survival.

Thus Goodwin claims that other living thing may be said to possess language and culture of a kind that is analogous to ours. Their cultural resources are an inherited stock of genetic information that enables them to “choose” effective ways to live and grow through interaction with their environments.

If this is true, Goodwin concludes, then not only are we wrong to believe that language, culture and the search for meaning are uniquely human attributes; we should also recognize what a lousy job we are doing of utilizing those gifts in comparison to other creatures.

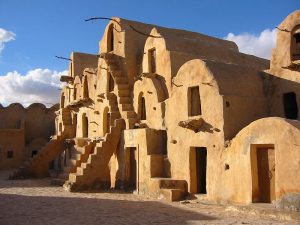

“Compared with our biological cousins, we have become extraordinarily clumsy in the creation of our artifacts. We do not use resources and energy efficiently as organisms do, and we often fail badly in the aesthetic quality of our artifacts.” As Goodwin puts it, “the human is the only creature who doesn’t know what he is supposed to be doing.”

Learning from Creation

So Goodwin’s prescription for change is that we should be humbly willing to learn from the rest of creation, which does seem to know what it’s supposed to be doing. Through bio-mimicry, natural design, architecture and city planning based on natural forms, we may return our culture and its artifacts to harmonious balance with the natural world.

My main criticism of this thoughtful and well-written book is that, if biology is not my area, then it seems probable that philosophy is not Goodwin’s. He himself alludes to the problem of early educational specialization based on the dualistic division of knowledge into “arts” and “sciences.” It appears that we have both suffered from it!

I have placed “text”, “interpret” and “culture” in quotation marks where they are applied to the activity of genes and organisms, but Goodwin doesn’t. The analogy, though plausible and thought-provoking, is nowhere near proven. It would take a far deeper discussion than Goodwin offers of what human “texts”, “interpretations” and “cultures are to justify removing the inverted commas.

Indeed the places where he does offer a philosophical basis for this view of science are the weakest in the book. Chapter 6 proposes that the little-known scientific work of the great German writer Johann Wolfgang Van Goethe prefigured a way of doing biology that can integrate quantitative and qualitative facets in a holistic and spiritually inspired vision.

Again, Goodwin offers enough to make this idea intriguing but not nearly enough to render it convincing. Bizarrely, almost half of the chapter is devoted to Goethe’s biography, and in particular, to his extravangant romantic life, (with extensive quotations describing one lover’s “large black eyes of the greatest beauty”, and her “easy Zephyr-like movements.”)

Discussion of the philosophical basis of Goethe’s thinking is thin. This is a pity. The German Idealist tradition of philosophy to which Goethe contributed, with its non-dualistic merging of nature and spirit and its evolutionary conception of consciousness seems to be a potentially fruitful source for grounding an ecological vision of science.

Ignores Healing

One of the many problems with Goodwin’s swift elision of the differences between human culture and potential biological analogues is that it ignores the healing possibilities inherent in the immensely greater complexity of human culture.

Suppose we accept Goodwin’s analogy and conclusions: the very fact that human culture can become so massively dysfunctional in its modes of adaptation to the physical world, in a way that other organisms appear not to be able to match, is itself tribute to the sophistication of human thought.

The immensity and ingenuity of the cultural and scientific information that we have amassed in printed and digital forms has created the technological instruments Book Reviews, with which we are degrading the biosphere. The human capacity for reflection on, development of, and conscious selection from our cultural resources is surely unique, even if one agrees with Goodwin that other organisms undergo analogous processes. And it is just these capacities for extremely rapid cultural evolution that give us hope that we can change course in time.

Survival is unlikely to lie in simply admitting what pathetic evolutionary failures our creations are in comparison with, say the elegant, functional beauty of the honey bee’s. It will also come from our ability to reach deep within our cultural memories, including our religious and spiritual traditions, and to rapidly actualize the wisdom that lies there for how we may live beautifully in an interconnected world.

Rabbi Julian Sinclair is a scholar, Jewish educator, and an economist. He holds a BA from Oxford University in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, a Masters in Public Administration from Harvard University and rabbinic ordination. He has been an economic analyst for the UK government, and Jewish Chaplain and Instructor in the Divinity School, Cambridge University.

Currently based in Jerusalem with his family, Julian is the author of “Let’s Schmooze: Jewish Words Today.” and co-founder of www.Jewishclimateinitiative.org.

2 thoughts on “Rabbi Sinclair Reviews "Nature's Due" And Its Complicated Biology”

Comments are closed.