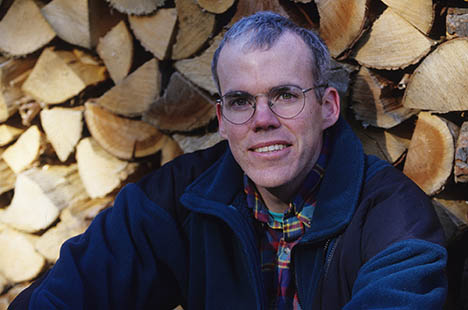

Deep Economy is probably the first economics book you’ll read that advocates for less economic growth. The book is framed around a simple, yet zealous premise – that what we need is Better rather than More. Author Bill McKibben believes, as do a growing number of economists, that we indeed have to choose between one and the other. He writes, “…growth is no longer making most people wealthier, but instead generating inequality and insecurity.”

Deep Economy is probably the first economics book you’ll read that advocates for less economic growth. The book is framed around a simple, yet zealous premise – that what we need is Better rather than More. Author Bill McKibben believes, as do a growing number of economists, that we indeed have to choose between one and the other. He writes, “…growth is no longer making most people wealthier, but instead generating inequality and insecurity.”

Stealing a page from the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, who in 1973 coined the phrase Deep Ecology, (an ecological philosophy that recognizes the inherent worth of other beings aside from their utility), McKibben writes, “We need a similar shift in our thinking about economics – we need to take human satisfaction and societal durability more seriously; we need economics to mature as a discipline.”

This is reminiscent of E.M. Schumacher’s Buddhist Economics, which I referenced in an earlier book review for Green Prophet. What is unique about Deep Economy is that the author understands that the only conceivable way to create a deep ecology is to address our culture’s obsession with economics first and foremost.

“The Fortunate Few?”

The reader needs to hang several preconceived notions at the door before McKibben’s argument begins to resonate. Firstly, that more wealth and greater Gross Domestic Product (GDP) automatically translates to a higher standard of living, and by extension – more happiness or satisfaction.

Almost immediately, McKibben undermines these assumptions. He writes, “The median wage in the United States is the same as it was thirty years ago. The real income of the bottom 90 percent of American taxpayers has declined steadily: they earned $27,060 in real dollars in 1979, $25,646 in 2005.”

Take a minute to digest this.

That means that all the talk of a growing economy and wealth is actually only being felt by a handful of the population (relatively speaking). This addresses the first assertion that greater GDP means we are becoming wealthier. Then McKibben continues, “new research from many quarters has started to show that even when growth does make us wealthier, the greater wealth no longer makes us happier.”

So not only are most of us not actually getting wealthier, but those ‘fortunate few’ who are, are not buying anymore happiness.

According to a paper written by Ed Diener and E.P. Seligman entitled, “Beyond Money – Toward an Economy of Well Being,” “researchers report that money consistently buys happiness right up to about $10,000 per capita income, and that after that point the correlation disappears.”

Always the realist, McKibben acknowledges that some people, particularly in developing countries where basic needs are still far from being met are better off with more money. He writes, “Up to a certain point, none of what I have been saying holds true. Up to a certain point, more really does equal better.” After all, a person has got to eat.

Supermarket Trance

Apart from debunking the correlation myth between GDP and happiness, he takes a close look at the modern food industry a.k.a. agribusiness as a case in point for how more is far from better.

According to a Harvard Business School professor McKibben quotes from in the book, “fifty percent of the world’s assets and consumer expenditure belong to the food system. Half the jobs too.”

Similar to Michael Pollan’s claims in The Omnivore’s Dilemma, McKibben cites “the average bite of food an American eats has travelled fifteen hundred miles before it reaches her lips.”

Transportation and the resulting dependence on fossil fuel are greatly responsible for the tragic misunderstanding that most well-meaning Whole Foods shoppers participate in.

“Organic” could also mean that the banana you just ate was actually imported from Chile at great expense in terms of carbon emissions and destruction of natural resources. If consumers internalized this, then more of our food would be grown locally and that would prove to be better for us and the environment than organic food.

Consolidation or another path to “More,” has numerous other dangers. According to the McKibben, “Four companies slaughter 81 percent of American beef. Cargill, Inc. controls 45 percent of the globe’s grain trade, while its competitor Archer Daniels Midland controls another 30 percent.”

For more about ADM and how economic consolidation leads to corruption, I HIGHLY recommend listening to this podcast (The Fix Is In) from This American Life.

Only a few companies control more than 70 percent of the fluid milk sales in the US, according to the book. All of this consolidation has been born out of economic efficiency and the unwavering pursuit of growth. McKibben indicates the high cost of all these efficiencies. He list several costs including: damage to communities and people who lose their jobs, safety risks both to employees and the food that they are responsible for processing, and the resulting pollution from the likes of one farm in Ohio McKibben claims produces 3 billion eggs per year.

Distributed vs. Centralized Systems

McKibben see hope through distributing economies instead of consolidating them. If the focus shifts from monetary growth, this Deep Economy can lead to prosperity through decentralization.

He points to the rise in farmer’s markets and community supported agriculture (CSAs) groups where “the farmers who come in from the country to meet their suburban and urban customers, the customers who emerge from their supermarket trance to meet their neighbors.”

McKibben writes that “Beside food, the most important commodity in our lives is energy.” The sheer scale of our energy production today is astonishing and creating a more distributed model of production does seem daunting.

Deep Economy doesn’t advocate an immediate switch from our current model of almost complete centralized energy production and transmission to an entirely distributed model…yet. Rather, the author suggests a middle ground, or “something in between the individual cell powering the individual home, and the great power station feeding the whole state.” After all, transporting a head of lettuce 1,500 miles makes about as much sense as transmitting electricity the same distance.

Centralized Energy

Deep Economy also addresses the heavy toll that centralized energy has had on the world along with its accompanying security concerns and deleterious effects on the environment. Gone are the days when solar power was code for, in McKibben’s words, “a set of panels up on the roof and a set of batteries down in the basement, supporting a grinning, graying hippie happy in his off-the-grid paradise.”

By distributing power generation amongst several options (even if we keep fossil fuels in the mix), we can hedge our bets should one central generation facility fail. We wouldn’t need to depend on building another power plant that would only be used as backup 10 percent of the year.

Today, Finland, the Netherlands and Denmark generate between one-third and one-half of their power through decentralized projects. The book is filled with examples of similar projects that are taking place in communities that rarely make the news cycle.

Their MacGyver like solutions to either food or energy scarcity are a testament to the adage that “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

What is fascinating about many of these examples is that they have no impact on their nation’s GDP, so they fly under the radar and in the face of what most American politicians on both side of the aisle are seeking – double digit economic expansion.

You don’t need a degree in economic theory or environmental engineering to appreciate Bill McKibben’s Deep Economy. But you do need an open mind.

Some interesting factoids I gleaned from the book:

- Nature attempted to set an economic value on ‘ecosystem services,’ such as pollination and decomposition, that had always be counted as free. The estimate was a whopping $33 trillion annually, far larger than the human economy combined.

- In an effort to ‘get prices right,’ professor Bob Costanza estimated that the real cost (based on damage from production and use of the environment) of a gallon (1 US gallon = 3.785 litres) of gasoline should be $7-$8/gallon.

- Exemplary of the merging between social sciences and economics, Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 despite the fact that his training was in psychology.

- People born in advanced countries after 1955 are 3 times as likely as their grandparents to have a serious bout of depression.

Read more by David Goldman:

Review on Strategy for Sustainability

5 Tips for PR Companies to Gain Credibility

Friedman’s “Hot, Flat and Crowded” – The Perfect “Green” Starter Book

***

David Andrew Goldman currently works as director of global communications at Expansion Media, an integrated PR/SEO firm that focuses exclusively on clean technology clients including Entech Solar, BioPetroClean, CASTion, AeroFarms, Airdye Solutions, Advanced Telemetry, Variable Wind Solutions, GreenRay Inc. and FreeGreen.com.

First of all…I’m ready to move to a farm….grow my own food, power up my house with wind and solar (and firewood) and live the distributed dream.

Secondly, in terms of happiness and wealth, the ancient saying “who is rich? he who is happy with his lot in life” really underscores the research McKibben writes about.

Interesting book review. Too bad the decentralization of energy resources is not really happening yet in Israel.