Poor management and water intensive crops to blame for what could be an irreversible desert in Syria.

“If desertification is not controlled, it threatens the land and our heritage,” Abdulla Tahir Bin Yehia, head of FAO in Syria, said. “The situation is terrible in Syria and has been worsened by the past years of low rainfall.”

According to the United Nations, 80 percent of Syria is susceptible to desertification, defined by FAO as “the sum of the geological, climatic, biological and human factors which lead to the degradation of the physical, chemical and biological potential of lands in arid and semi-arid zones, and endanger biodiversity and the survival of human communities.”

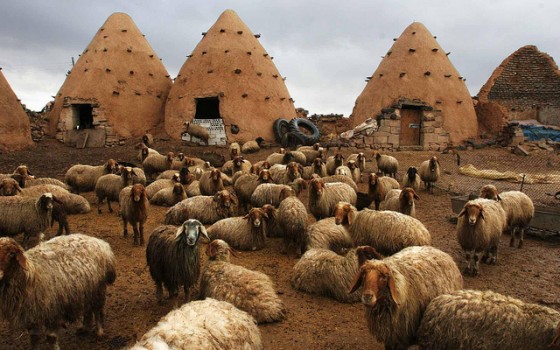

Three years of drought have destroyed crops and livestock, ruining the livelihoods of thousands of farmers and displacing some 300,000 rural families to cities. This year, however, there has been enough rainfall for the FAO to stop describing the situation as a drought, but uneven rainfall distribution has caused continued, widespread crop failure, putting the more than one million people already bordering on the poverty line into further jeopardy.

The World Food Programme (WFP) on 13 June said it had begun distributing food rations to 190,000 people in the eastern provinces of Hasakah, Deir al-Zor and Raqqa, but that another 110,000 people also required emergency food aid. WFP said a lack of funds was preventing it from distributing rice, oil, flour, chickpeas and salt rations.

Causes for drought man-made

Syria’s drought over the past three years and its increasing desertification is due to a combination of man-made and natural factors, experts say.

“There are natural causes beyond anyone’s control, as well as man-made causes,” said Douglas Johnson, a desertification expert at Clark University in the US. “In the Middle East the cause is almost entirely human activity. But that’s a simplistic statement because there is almost always an interaction with the natural environment. It is normal for the environment to fluctuate; some areas of desert may have no rain for four years, for example,” he said.

This has been the case in Syria, but has been compounded by poor water planning and management, wasteful irrigation systems, over-grazing, water-intensive wheat and cotton farming and a rapidly growing population.

Agriculture accounts for almost 90 percent of the country’s water consumption, according to the government and private sector, so the policies governing it are critical to the preservation of the land and efficient use of water.

“Traditionally, communities had methods to avoid desertification, such as rotation or leaving an area unused. This allowed the vegetation to grow back,” said Bin Yehia. “But modernization and centralization takes the decision out of their hands.”

He said rising demand for meat from a growing and increasingly affluent population was also contributing to land degradation.

“Syria’s estimated livestock stands at 14-16 million. But it is only that low because many died during the drought. Prior to this the national herd stood at around 21 million. We need to study how much livestock the land can take,” said Bin Yehia.

Desertification can be irreversible, such as when an aquifer dries out and the land sinks in on itself, destroying the structure. Flora and fauna species that lose their natural habitat can become extinct.

Bin Yehia is optimistic that much of Syria’s desertification can be reversed – but only if action is taken now.

“It is possible to reclaim pasture and on a large scale. But it is a long-term project that would take five to 10 years,” he said, adding that it needed more funding, studies and awareness-raising.

An experimental drip?

As well as reclaiming pasture, experts suggest local communities should be more involved in making land use and herd size decisions. An experimental drip irrigation project in the central district of Salamieh has spread to 52 villages as farmers realized they could use 30 percent less water to produce 60 percent more output.

Syria, a signatory to the 1994 UN Convention to Combat Climate Change, has drawn up a National Programme to Combat Desertification with the support of the UN Development Programme.

The country designates its land according to five zones, where zone five is the driest. Since the early 1990s, cultivation of land in zone five has been banned.

With the support of FAO, protected areas have been created around the eastern settlement of Palmyra, but the pilot project has not been rolled out on a large scale. A future plan, for which FAO is seeking funding, aims to claim back pasture in Homs governorate.

Read more on Syria:

Syria Officials Brainstorm on Renewable Energy

Syria’s President Appoints Woman As New Environment Minister

A Nature Peace Park Won’t Work Without Syrian-Israel Peace First‘

I was looking at Syria on Google Earth and I saw many striations in the northern part of the desert. I couldn’t tell if they were ancient or modern, but a few photos show what appear to be tree plantations. I was wondering if Syria is undertaking a massive revegetation program. I also noticed that along the Syria/Lebanon border, there are trees in Syria and not in Lebabnon. I am sorry to hear that land is being degraded, I was hoping Syria was doing a better job than some places in maintaining vegetation on the land.